Merchant Cruisers: The Spark

Part One of the Cruiser Revolution

Like using the button below; only I can see who you are.

An enterprising British businessman, always trying to find a better way to make more money while spending less, started a revolution in naval architecture that only ended half a century after he died. His name was Isambard Kingdom Brunel (such a name!), who popularized the dimensioned mechanical drawing (inventing the concept of tolerances while doing so) and made a faster, long-ranged steamship in 1838.

SS Great Western.

The Americans built the first steamship to cross the Atlantic, Savannah managing the crossing in 1819. On that 29-1/2-day trip, she had her engines running for about 80 hours because she couldn’t carry enough coal for more. Twenty years later, Brunel’s Great Western crossed the Atlantic in 15-1/2 days, running under steam all the while.

That was a problem for the navies of the world.

While 19th century merchant fleets could innovate and build new ships as quickly as new equipment was invented, especially power plants, naval forces were restricted by the needs of armor plate, crew training on a large scale (especially the technicians needed for the engines), and weapons. Shipping and passenger lines could afford to—indeed, could ill afford not to—buy the latest in propulsion systems, especially the triple-expansion engines first appearing in 1874, and the rotary turbines in 1884. New engines, steam handling improvements, hull shapes and other advancements meant that the ever-faster commercial ships could carry more passengers and cargo more quickly, putting a premium on faster transportation and increasing the value of the cargoes, at a higher price for both travelers and shippers.

What a steamship line could innovate with a single ship in a year could take a navy a decade.

Great Western was the first transatlantic steamship that needed no sails for its complete crossing, but carried them for emergencies and stability in heavy seas. She started service in 1838 as an extension of Brunel’s Great Western Railroad, who had tremendous financial resources to back her up. A wooden-hulled paddle wheeler, she was the largest ship of her time, and was without peer in speed, offering fifteen day crossings (at just under eight knots) from Bristol to New York, when eighteen days was good time for the fastest steam warships.

As a blockade runner or a commerce raider, Great Western or a ship like her might have been dangerous.

In 1858, SS Great Eastern entered service, also built by Brunel. For a half century she was the largest ship in the world, six times longer than any rival afloat when she was launched. Brunel equipped her with sails on seven masts, five funnels for her four steam plants, paddlewheels and a screw propeller, and could carry 4,000 passengers from England to Australia without stopping for coal (though Brunel never used her on that route for commercial reasons). She was also fast, routinely crossing the Atlantic in ten days or less.

For the navies of the world, she was yet another foul harbinger of things to come.

As an armed raider, Great Western would have been a menace to shipping lanes that no warship could catch: as a blockade runner, she would have been practically immune. For sailing ships, endurance and thus range had been determined by the amount of fresh water that could be carried so that the size of the crew and the ship were the most important factors. Most long-distance sailing vessels could last maybe thirty days on full rations, about a gallon per man per day. For steamers, the volume of coal was the determining factor in these calculations. Early steamers could last perhaps a week on full steam propulsion, which few did. Many early steam warships used their engines only for maneuver in port, close to shore or in combat.

Great Eastern and similar ships could not only outrun but outlast every warship afloat.

While Britain had more than enough ports and colonies to support a major commerce raiding offensive and feed herself in peacetime, her global sea lanes that provided most of her foodstuffs made her more vulnerable to just such raiding than were her rivals. No nation could afford to build and maintain as many ships as Britain. But Britain, herself, could not afford to build as many commerce-and sea-lane-protecting, long-distance warships of a size like Brunel’s giants…vessels she might ultimately need in the event of a war with a major seagoing power such as France, Russia or the United States—or burgeoning Germany or Japan. Cruisers of all kinds were the least expensive—or so it was thought—way to ensure the safety of her lifelines. To counter these threats—both fast commerce raiders and blockade runners based on merchant ships—the navies sought to create new groups of the middling class of warships: cruisers.

The successful career of Great Western and Great Eastern signaled the beginning of the purpose-built cruiser evolution.

While these purpose-built ships were under construction, there was an expedient: the merchant cruiser. The theory was that a fast merchant ship, armed with guns, could catch other fast merchant ships, negating their speed advantage. This, in theory, could be done quickly and efficiently. As a test of the concept, the Royal Navy looked to the merchant service for a suitable platform.

And found one.

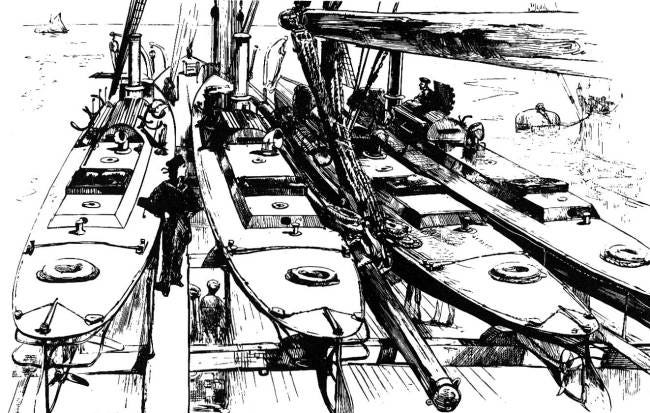

Built for the Far East trade as SS British Empire, under the house flag of the British Shipowners Company Limited of Liverpool, the Royal Navy commissioned HMS Hecla in 1878 as either an Armed Merchant Cruiser (AMC) or a torpedo depot ship (sources differ) after her purchase by the Admiralty at a cost of £120,000. Hecla was described as “a fine four-master vessel, carrying thirty Whitehead torpedoes, launched from tubes below the waterline plus a complement of no less than six specially constructed steam-powered torpedo boats, each measuring sixty feet in length.”

AMCs were also called Auxiliary Cruisers or just Merchant Cruisers.

Initially, Hecla's main armament comprised six Nordenfelt one-inch quick-firing guns. Their successful operation resulted in similar guns being deployed at strategic ports across the British Empire. The torpedo boat tender/cruiser theory perished before WWI, probably before the Boer War, but the RN rebuilt Hecla in 1912 and used her as an AMC in WWI. Hecla was successful as a torpedo boat tender that never fired a shot; as an AMC…

The heyday of the AMC was between 1879 and 1918.

“Building” an AMC was easy: strip a merchant/passenger ship of her civilian luxury appointments, commission her in a regular navy, arm her and put naval, not merchant, sailors aboard. Unfortunately, the Armed Merchant Cruiser was obsolescent by the time anyone started building them, and with the armored cruiser appearing not long after Hecla was commissioned, their roles, as first imagined, became perilous. They used AMCs in the first Sino-Japanese War, the Russo-Japanese War, the Italo-Turkish War, the Libyan War, both Balkan Wars, and the Spanish-American War. All with varying degrees of success, and all on a fairly small scale. No one was as invested in AMCs as Great Britain.

Look upon the AMCs as Mahan’s Bastard Children Before the Submarine.

While AT Mahan recognized the importance of bases and sea lines of communication, the kind of war that the AMCs engaged in primarily—commerce raiding—was anathema to his philosophy of decisive naval battle and his notions of discipline. The submarine, which was just a toy when the AMCs became popular, was looked upon with great derision by Mahan and his peers because…well, commerce raiding was for pirates, not sailors.

WWI was the AMC’s best war.

After a battle that caused heavy damage on both sides, RMS Carmania sank German auxiliary cruiser SMS Cap Trafalgar near the Brazilian island of Trindade in September 1914. By coincidence, Cap Trafalgar was disguised as Carmania. But the armored cruisers and other purpose-built warships of equal speed could outfight them, as HMS Otranto found out at Coronel in November 1914. But the RN’s 10th Cruiser Squadron, patrolling the northern outlet of the North Sea for most of WWI, enjoyed a great deal of success in those long patrols.

However, most AMCs were just shell bait by WWII.

The RN knew this, but the AMCs were available when other warships weren’t. While patrolling north of the Faroe Islands in November 1939, HMS Rawalpindi encountered German battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. Despite being hopelessly outgunned, Captain Edward Coverley Kennedy, RN, of Rawalpindi decided to fight, rather than surrender, as demanded by the Germans. He was heard to say "We'll fight them both, they'll sink us, and that will be that. Good-bye,“ as he signaled the German ships’ location back to base.

The German warships sank Rawalpindi within 40 minutes.

She scored one hit on Scharnhorst, causing minor splinter damage. Over two hundred men died on Rawalpindi, including Captain Kennedy. The Germans plucked 37 men out of the drink. Another AMC, HMS Chitral, rescued another 11 men. The Germans, however, had to abort their raiding mission, as Rawalpindi compromised their position, so she did her job.

Captain Kennedy was posthumously Mentioned in Dispatches.

In November 1940, Acting Captain Edward Fegen in HMS Jervis Bay was one of three escorts for convoy HX 84, when pocket battleship Admiral Scheer attacked the convoy. Though Admiral Sheer sank Jervis Bay and five ships of the convoy after a running gunfight lasting just twenty minutes, Jervis Bay’s brave stand (and a signaling bluff to phantom supporting ships over the horizon) enabled the other 33 ships in the convoy to scatter and escape.

Britain awarded her master a posthumous Victoria Cross for his actions.

The Armed Merchant Cruiser was a throwback to the time when merchant ships were armed against pirates. But as expedients went, they had some success in roles like blockading when they were up against ships like them. But against warships, they were helpless, but not useless, as Jervis Bay and Rawalpindi showed. The last AMCs were converted to troopships or scrapped by 1944.

The Safe Tree: Friendship Triumphs

No; nothing whatsoever to do with merchant cruisers, just the last of the Stella’s Game Trilogy.

The friends finally find out who’s behind all the shenanigans that have been dogging them since high school, but at a price. From your favorite bookseller or from me if you want an autograph.

Coming Up…

Strategy and Luck; Culture and Geography

The Ethics of Firebombing

And Finally…

On 10 February:

1906: HMS Dreadnought is launched in Portsmouth, England. Dreadnought was a revolution in warship design, as an “all-big-gun” warship, but still carrying torpedoes. “All-big-gun” means her main and auxiliary batteries were of just two calibers. She missed the battle of Jutland, but she was the only battleship to sink a submarine, ramming SM U-29 in March 1915.

2014: Shirley Temple Black dies in Woodside, California. Affectionately known as a moppet of the feel-good Golden Age of Hollywood, Shirley Temple’s roles grew fewer as she became a young woman, her talents not able to carry her into grownup roles. She left Hollywood in 1950 for life at home and university, and later becoming a delegate to the UN General Assembly under Nixon, ambassador to Ghana and Chief of Protocol in the Ford administration, and ambassador to Czechoslovakia under George HW Bush.

And today is NATIONAL HOME WARRANTY DAY. For those of you who have these things, you know what a mixed blessing they can be. For those who don’t, be very careful who you hire to cover your whole house. It may sound better than it is.