The Invention of Microbiology

Science, like history, often depends on talented amateurs

Like using the keys below; only I can see who you are.

This is a riff on a History Today article by Matthew Lyons in October 2025.

History names Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, born in Delft, Dutch Republic, on 24 October 1632, as the father of microbiology and a pioneer in microscopy. While Leeuwenhoek was the first to report on microorganisms, the history books are short on just why this talented amateur with no formal training in biology or science at all, came to “invent” microbiology.

Magnifying lenses date back to antiquity. Nero watched gladiators through ones made of emerald. Leeuwenhoek first saw crude lenses when he was an apprentice bookkeeper in the cloth trade, where thread counters used them to judge the quality of textiles. Leaving his apprenticeship in 1654, Leeuwenhoek lived and studied most of his adult life in a house he bought in 1655, on a street named Hyppolytusbuurt, opening a draper’s shop there. In the late 1650s, Leeuwenhoek started making small lenses himself.

In 1660, Leeuwenhoek became a chamberlain for the sheriffs in the city hall, maintaining the premises, heating, cleaning, opening for meetings, performing duties for those assembled, a position he would hold for almost 40 years. In 1669, the court of Holland appointed Leeuwenhoek as a land surveyor. Gradually, he combined that job with one as the “wine-gauger” (official measuring the contents of casks) of Delft.

By the early 1670s, Leeuwenhoek was building compound microscopes (devices using multiple lenses), invented around 1590 by Dutch spectacle makers Hans and Zacharias Janssen. What drove a civil servant and businessman to do it?

My own impulse and curiosity…there are in this town no amateurs who, like me, dabble in this art.

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

He worked with his microscope when his various jobs allowed. With nothing else to guide him, Leeuwenhoek studied what he could get easily: his own sweat and blood, lice and their eggs, leaves, molds, skin, hair. He developed his own comparative measurements: a grain of fine sand, a hair from his head, a silkworm thread.

In the summer of 1674, Leeuwenhoek took a water sample from a boggy inland lake near Delft. He was astonished to discover that it contained what he called ‘kleijne diertgens’, little animals, or animalcula.

The motion of most of them in the water was so swift, and so various ... that I confess I could not but wonder at it…[Some] were above a thousand times smaller than the smallest ones which I have hitherto seen in the rind of cheese.

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

Leeuwenhoek borrowed a method for counting sheep to count flocks: estimate the number of sheep walking alongside one another and multiply that by the estimated length of the flock. On that basis, there were 2,730,000 animalcula in each drop of water.

Although he considered himself a businessman and not a man of science, the spirit of his time compelled him to tell others what he had discovered. It took several letters from Leeuwenhoek to the Royal Society in England to get them to notice his discovery. ‘We had such stories written [to] us from Holland and laughed at them’, John Locke said. Finally, on 9 October 1676, Leeuwenhoek pulled all his observations together in a long letter they could not ignore. It took them three attempts to replicate the findings. The Society dispatched Irish physician Thomas Molyneaux to watch Leeuwenhoek at work. “His only secret,” Molyneaux reported in March 1685, “is making clearer glasses, and giving them a better polish than others can do.”

Over the course of his lifetime, Leeuwenhoek may have made five hundred microscopes, some of which may have been capable of 500x magnification. Though considered a scientific dilettante, by the end of the 17th Century Antonie van Leeuwenhoek had a virtual monopoly on microscopy and microscopic study, having accurately described red blood cells in 1674, and discovered human spermatozoa in 1677 (though he believed they were merely preformed humans).

Not bad for an amateur.

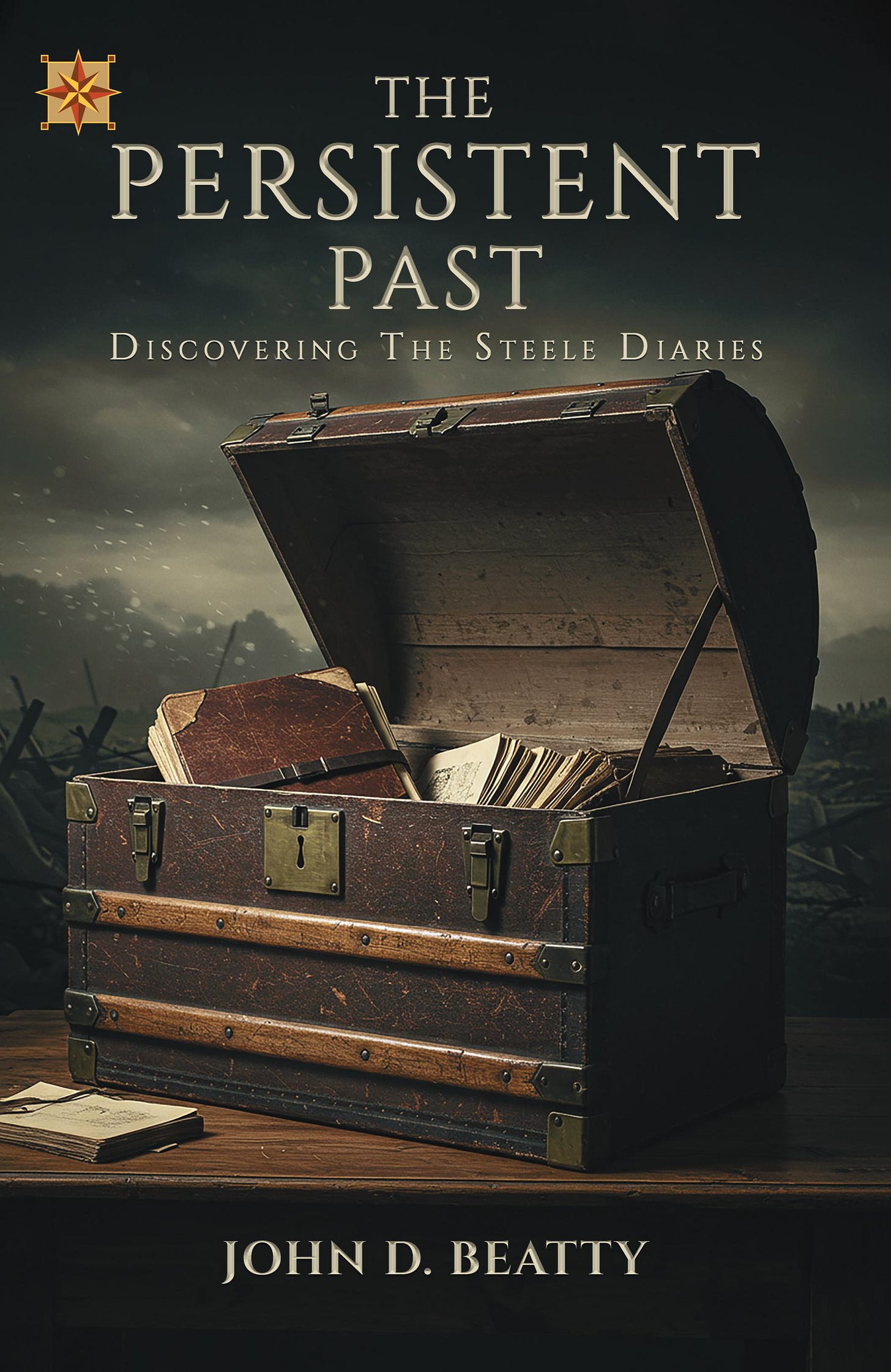

The Persistent Past: Discovering The Steele Diaries

While Dr. Curtis Durand is no amateur historian, his daughter Maria is but thirteen when she goes to work transcribing the Steele Diaries. Will she turn pro and stick with it, or just walk away from the grueling, painstaking toil needed to turn raw sources into discoveries?

This is how history books—and historians—are made.

And Finally...

On 10 January:

49 BC: Julius Caesar crosses the Rubicon, a small stream in northeastern Italy that served as a boundary between the province of Cisalpine Gaul and Italy, with his army. Doing so constituted a declaration of war against the Roman Senate and triggered a civil war that ended with Caesar holding absolute power after defeating all his opponents.

1927: Fritz Lang’s silent film Metropolis premiers in Germany’s most prestigious theater, the UFA-Palast am Zoo in Berlin, Germany. Based on Thea von Harbou’s novel of the same name, the film received mixed reviews for its melodramatic (nonsensical) plot, although the visual effects and art direction earned well-deserved praise. Although cinephiles now hail it as a groundbreaker, no complete copies of the original 153-minute film exist, but reconstructions abound and researchers occasionally discover lost segments.

And today is NATIONAL CUT YOUR ENERGY COSTS DAY, which may commemorate either the founding of Standard Oil in Cleveland, Ohio, on this day in 1870, or the Spindletop Hill gusher near Beaumont, Texas, on this day in 1898. Pick your poison…

'Metropolis', with the modern musical score, is fascinating to watch.

Granted I can't watch the whole thing in one sitting, it's well worth watching over time.

I think the movie does a good job of expressing some of the sentiments that we are feeling today.