Money and World War Two

Something had to buy all those weapons, and food, and uniforms, and...

Like if you want using the keys below; only I can see who you are.

Absolutely no one thinks about money and World War Two at the same time, until now. Why now? Because I am.

The Great Depression strained societies and budgets around the globe.

The economic catastrophe of 1929 produced political tensions that grew throughout the 1930s. World War II was a result. In September 1939, Germany’s invasion of Poland triggered war among the principal European powers. Finances, already strained by the last global war, would be strained again.

The US Treasury and the Federal Reserve planned how to finance the war and market bonds for financing the war before it started.

The plan, that had to have begun before Pearl Harbor, called for financing the war as much as possible through taxation and domestic borrowing through bond sales (a bond is, after all, a promissory note). Paying for the war through levies on current incomes would minimize inflationary pressures, promote economic expansion during the war, and promote economic stability when peace returned.

December 8, 1941.

This was the most memorable day at work for a career employee of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. She and her coworkers listened to the radio as President Roosevelt described the attack on Pearl Harbor and announced Congress’s declaration of war against Japan. Then, seven men rose from their desks to volunteer for service.

The Second World War cost the United States about $304 billion.

The Roosevelt Administration, fresh from the complexities of creating the New Deal, paid the bill through an equally complex mix of taxation and borrowing. Before the war, most Americans paid no income tax, because the median wage was $1,231 (1939), but the personal tax exemption was up to $1,500. The Revenue Act of 1942 changed that, by lowering the tax exemption to $624 a year. Immediately, 13 million new taxpayers and $7 billion new tax dollars appeared. Paying your taxes became patriotic, as exemplified by Irving Berlin's flag-waving 1943 hit, "I Paid My Income Tax Today!" And there was more money to come, because many of those new (and old) taxpayers would soon earn more, much more, from the higher wages paid by war-related industries, which collected taxes through withholding for the first time in American history.

Finance formed a foundation for the war effort.

Before the war, America’s military was small, and its weapons were obsolescent. The military needed to purchase thousands of ships, tens of thousands of airplanes, hundreds of thousands of vehicles, millions of guns, and hundreds of millions of rounds of ammunition. The military needed to recruit, train, and deploy millions of soldiers to theaters of action on six continents. Accomplishing these tasks entailed paying entrepreneurs, inventors, and firms so that they could purchase supplies, pay workers, and produce the weapons with which America’s soldiers and sailors would defeat its enemies. Military expenditures rose from a few hundred million a year before the war to $85 billion in 1943 and $91 billion in 1944.

To stimulate war production, those same industrial employers received unprecedented help from the government.

1940 legislation allowed full amortization of war-related plant and equipment investments over just five years. Corporations could thus shelter otherwise taxable profits. Anti-trust prosecutions eased, while military procurement agencies issued contracts on a cost-plus basis, with guaranteed profits for the contractor. It was a system, in the words of historian David Kennedy, "…beyond the most avaricious monopolist's dreams."

It worked.

Corporate profits went from $6.4 billion in 1940 to $11 billion in 1944, while the machines to win the war got made in unbelievable abundance. The money-raising system worked so well, in fact, that the government worried too much money would cause inflation. Rationing some commodities and instituting wage and price controls were among the ways the administration kept that from happening.

Of course, there were the bonds.

Financing to pay for the war came mostly by borrowing from the American people through the sale of war bonds, which raised about $50 billion. Another $150 billion came from financial institutions. During the war, commercial banks alone increased their Treasuries holdings from $1 billion to $24 billion.

And the Federal Reserve helped.

When the United States entered the war, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve stated that the Federal Reserve System was “. . . prepared to use its powers to assure at all times an ample supply of funds for financing the war effort. Financing the war was the focus of the Federal Reserve’s wartime mission. In 1939, the Reserve Banks employed about 11,000 individuals. In 1943 and 1944, employment in Reserve Banks hit a wartime peak of over 24,000. The War Manpower Commission declared Reserve Banks’ efforts to be essential to the war effort. So, Reserve Bank employees were not subject to the draft, although hundreds of Federal Reserve employees volunteered for military service.

Bonds and stamps were the most common ways to invest in the Arsenal of Democracy.

The Treasury and Federal Reserve marketed options for everyone to help pay for the war . Everyone from children and housewives to large corporations with temporarily idle funds had ways to invest for the duration of the war. Reserve banks organized Victory Fund committees and established plans to market war bonds and stamps in cooperation with commercial banks, businesses, and volunteers. Interest rates were pegged at low levels to keep costs down. Reserve banks bought Treasury bills at three-eighths of a percent per year, far below the typical peacetime rate. They also reduced their discount rate and created a preferential rate for loans secured by short-term government loans that were in effect until 1948.

When too much money chases too few goods, prices rise (sound familiar?).

War increases incomes, employment, and the money supply, while cutting down on consumer goods. To prevent price increases from undermining the war effort, regulations on the prices, wages, and rationing of scarce commodities and consumer durables began, as well as the regulation of consumer credit. Installment loans were limited to twelve months. Single-payment loans were limited to ninety days.

Blood and treasure.

While the Fed helped on the home front, scores of Fed employees gave their lives for their country. No doubt more than a few Fed women volunteered to serve. Men from the Federal Reserve fought and died in the hedgerows in Normandy, the Bulge in Belgium, the mountains of Italy, and the beaches of the Pacific. Just paying for the war with treasure wasn’t enough.

To paraphrase Churchill, blood, sweat, toil and tears…and $304 billion.

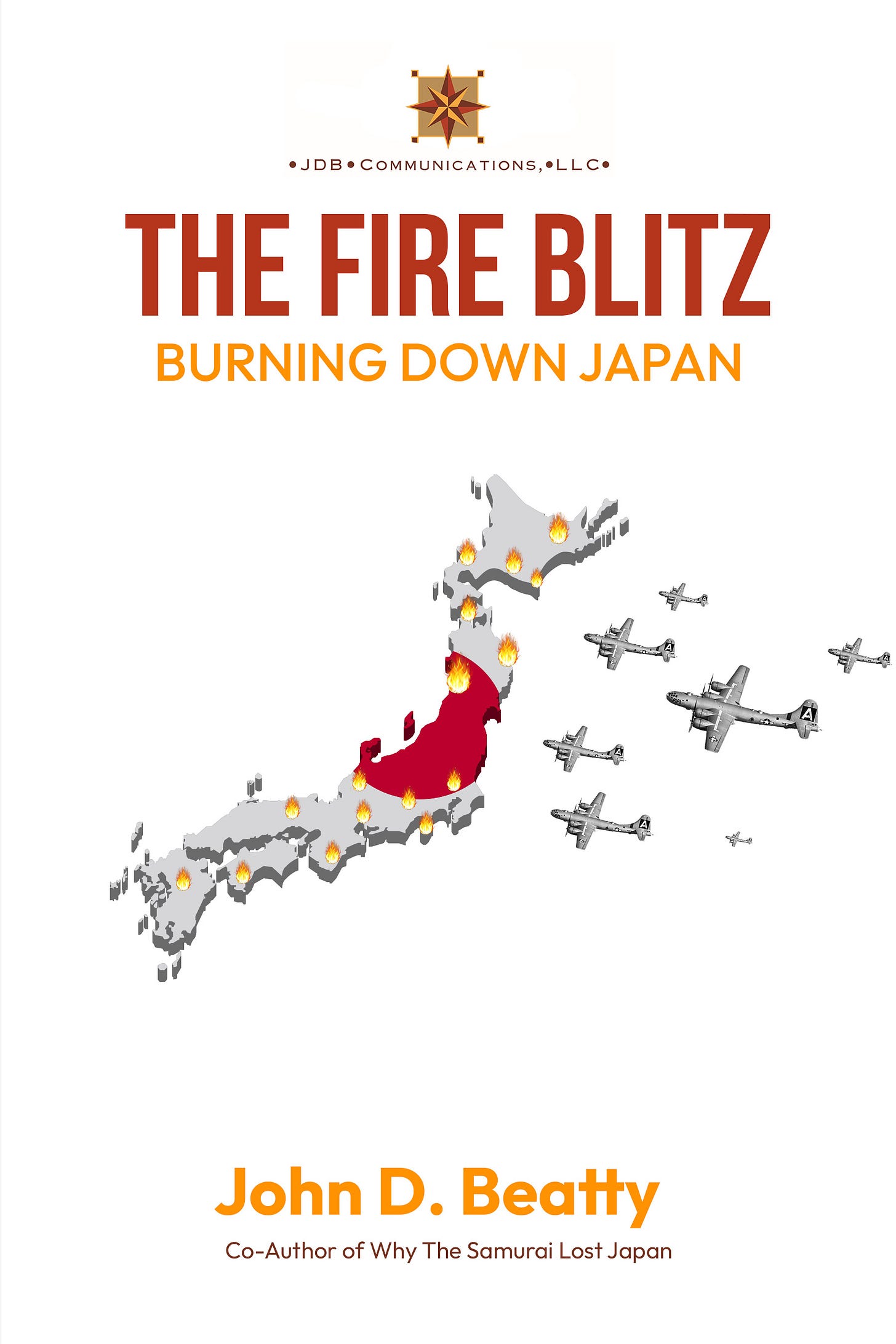

The Fire Blitz: Burning Down Japan

The Fire Blitz doesn’t address financing directly, but it talks about how Japan’s poverty made its preparations for war more challenging. Unable to afford the kind of research and development the Americans could would have dire consequences in 1945.

War is expensive, as everyone knows. World War Two, arguably, was the most expensive ever. The Pacific bombing campaign was the most expensive of that war. Available from your favorite bookseller or from me if you want an autograph.

Coming Up…

What Made Japan Do That?

Clare, Shannon, and Me

And Finally...

On 18 May:

1860: The Republican Party nominates Abraham Lincoln for president in Chicago, Illinois. 1860 was a highly polarized election season that saw the Democratic Party nominate three candidates, assuring Lincoln’s election in November. You think the country’s polarized now…

1973: Jennette Rankin dies in Carmel-By-The-Sea, California. Rankin was the first woman elected to the House of Representatives (Montana), and the only Congressperson to vote against both declarations of war in the 20th Century, WWI and WWII, both of which she recognized as merely symbolic.

And today is NATIONAL NO DIRTY DISHES DAY. This is the one day of the year when everyone should avoid even creating dirty dishes, the one thing in every household that everyone hates. So, go out, use paper plates, or fast. Three ways to “celebrate” today.