Leviathan Awakening

The Birth of American Military Doctrine

Like if you want using the keys below; only I can see who you are.

By 1897, America had fought six wars with foreign powers, hundreds with its own aboriginals, and had maintained the oldest standing military academy in the world. American military theorists had read, translated and copied French handbooks, but they had also developed their own doctrines, especially in artillery, mounted and light infantry operations. Most especially, the Americans departed from European military policy.

Militias and Continentals

The American Army had started life literally under fire, and didn’t have a great deal of time to develop formal doctrines or bodies of theory. But they had access to the unrelenting and long militia traditions that formed the basis of American land warfare. For centuries, colonists had a military doctrine that never failed them:

• Fight for as long as possible, as far away from the centers of population as possible;

• Fall back on the strongest defensive positions available, leaving little behind for the enemy;

• Organize powerful forces far to the rear to relieve the frontier militiamen;

• Strike the enemy where he lives when strong enough to do so.

Except for the last step, this doctrine was largely what Washington used for eight years of war against the British. The first phase resulted in a long buildup around Boston, bottling up the strongest British forces in the hemisphere for nearly a year. When Henry Knox, a self-taught artilleryman, arrived to bolster the siege with a substantial artillery train, the British rethought their holding strategy and withdrew. When the British returned and invaded New York, Washington kept his army moving as much as he could, trading space for time while trying to harden his men on the march. In the second winter of the war, Washington may have been feeding his men leather and parched corn, but he still had offensive plans. While the British and Germans wanted to wait out winter, Washington successfully struck at isolated outposts of Trenton and Princeton. Still green, his men were learning. During this period, a new army, a proper army, was building in the rear. Dubbed “Continentals,” these men enlisted for longer periods than Washington’s militias, whom he often had to beg to stay in ranks beyond their terms. They also joined up understanding that the Army could deploy them wherever needed, which was another departure from the militia tradition. It was these two basic changes that allowed the Continentals to be trained and equipped to be the equals of British line infantry by the end of the war. The survival of Washington’s army was the epitome of the way Americans would say that they preferred wars to be fought for the next two centuries. Standing armies were to them anathema and believed European-style wars improbable. They felt there would always be time to build adequate forces, and Americans would always rise to the task. Nearly two hundred years would pass, with most Americans paying no attention to military affairs: upon reading stories about substantial pay and personnel cuts in the 1930s to meet Depression fiscal demands, East Coast socialites thought the Army was disbanded after 1919.

Early American Strategic Doctrine

Both the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution had provisions for standing military organizations, but left a great deal to the discretion of Congress. As a result, the first Army organization provided for a standing army of fewer than 100 men and officers and no naval force at all. American military policy in the 1790s centered on internal security, believing (rightly) that Britain and Spain had other things to worry in the wars with the French than with the Americas. But the Indians were still quite active, and in the Ohio country the first test of American military policy under the Constitution worked. Anthony Wayne’s Legion of the United States met and destroyed the threat the Army designed it for, after the militias had failed in their quest to do the same thing. From this event, and the successful mobilization during the Whiskey Rebellion, the American policy of national defense was to be unchanged from its colonial roots. This pattern wasn’t so different from the British habits of smaller standing armies, but it differed from Continental practice, which kept larger armies than the Anglo-Americans, if smaller navies.

Afloat, the Americans departed from all other practices.

Before 1794, the Americans didn’t own a single naval vessel. By 1800, two of the most powerful cruising vessels afloat, the large and technologically advanced frigates, were integral to American strategic policy. Their role was to make any power think twice about picking a fight with the US, and, using ruthless commerce raiding, slow any cross-ocean invasion. Naval policy dovetailed with overall land war strategy: empty lands that let the invaders come, where they would find nothing but militiamen in blockhouses and devastation until the Americans rose to smite the invaders. The states would foot the minor bills of organizing the militia. All the while, the Army grew, almost in proportion to the greater armies that were then fighting all over Europe. Dispersed in isolated outposts, soldiers often had to hunt and grow their own food, and were years in arrears with their pay. But the officers were learning their trade in the American way—by experience. Realizing that the country needed engineers, Congress founded a school in 1802 on the banks of the Hudson River aimed at training surveyors, telling the Army to run it while Congress decided who would attend, who would get commissioned and what they would do. They called it West Point.

1812, Mexico and Indians

The War of 1812 demonstrated the inadequacy of American policy. The most active fronts in the 1812-15 conflict were, in order, the Niagara region, the Atlantic coast, and the Great Lakes. All three vindicated American strategic policy, yet the conflict was as good as lost. Most of the war was a holding action; the Navy had a better win/loss record than the Army; administrative and policy blunders made the militias, as organized, nearly useless outside their communities.

Strategically, the War of 1812 was a rousing success.

The Americans were never at a loss for either powder, shot or men (even if they were in all the wrong places). Lawrence’s naval victory on Lake Erie in 1813 and the invasion of Ontario by militiamen in 1814 crushed Canada’s hopes of ever being more than a bit player in North America. The best-known victory at New Orleans came after the war was over and secured the Louisiana Purchase above contestation. America had again not lost against the greatest empire on Earth, if barely. The conflict spurred great reforms in military policy.

The standing Army tripled in a generation.

Artillery standardized on the French pattern, enlarged, and reformed twice between 1816 and 1846.

Pay became standardized.

West Point revitalized and indeed militarized (even if the Army did not really control it yet), and the militia laws reformed.

By the time war started with Mexico, the American army, though small, was a Napoleonic jewel, unfortunately dispersed fighting Indians for most of its existence. No colonel in command of a regiment in 1846 had ever seen his entire command at once. But in Mexico, the highly professional junior officers, dominated by West Point graduates, demonstrated what could be done with small armies of trained professionals backed by a few militiamen against peasant levees led by semi-skilled aristocrats. Again rising to the occasion, the Army vindicated American military policy that was essentially unchanged since Washington’s day. The Army that captured Mexico City went home and was again at least partly disbanded, but this time it was different. Most infantry and cavalry units broke up, but the artillery expanded, if slightly. Indian fighting was a matter for foot soldiers, but the American artillery showed a propensity for victory that had been unanticipated. While the Army did not stop buying artillery, they entirely canceled musket orders.. Cavalry horses sold for pennies on the dollar or the gunners took them. While scattered again in the trans-Mississippi, the Army’s artillery still thrived.

Professionalist vs. Volunteerist

The controlling brake on American land warfare theory has always been the debate about how large the Army should be, and who should be able to run it and the debate split into two camps. First, the professionalists held that the only way to conduct war with the least blood and treasure is to build a large standing army that answers the call whenever and wherever needed. Volunteerists argue American only needed a nucleus, a hard core of professionals to train and leaven the volunteers when they are called up to meet whatever emergencies occur. George Washington argued for an American regiment in the British Army before the Revolution; Parliament turned him down because the Horse Guards, who controlled commissions from London, would have been hard pressed to approve Americans of unknown family ties as officers. He pressed Congress throughout the war for a body of regular troops and eventually got the compromise Continental Army; formed by the states, trained uniformly, and signing on for long terms. Washington’s efforts were rewarded by the Continentals, but compromised under the Constitution, which was ambiguous about the place of the Army in the structure of government. After the Civil War, Emory Upton wrote extensively about American military policy, and recast American infantry tactics based on the Civil War experience. Upton, in Military Policy of the United States, held that only a professional army could address the international challenges that he saw coming. Upton was an influential advocate for a general staff in the United States, and for the reorganization of the volunteers into a trained and standing reserve along Prussian/German lines. The volunteerists’ earliest champion was ideological purist Thomas Jefferson, who saw the American ideal as being a patrician elite/yeoman farmer who needed only an occasional practice meeting to ensure that his flints were sharp. Jefferson, enamored of the French Revolution and certain that the ideals would sweep the world in his lifetime, became disillusioned with his vision of an all-volunteer force when he learned of the perversions of Republican ideals under Napoleonic France, and experienced first-hand the harsh military realities of the Barbary Wars. John A. Logan, a pre-Civil War Congressman and successful wartime general, refuted Upton’s call for a professional army at every opportunity, and fought Upton’s forward-looking reforms with his considerable Grand Army of the Republic muscle.

Who, What, or Where?

War on Armies

The first and most successful principle was based on fighting against the military forces of the enemy. Logic dictates that if there is no enemy army, there is no opposition. Though logically simple, practical reality defies it. Destroying enemy armies alone is nearly unheard of. However, in at least two cases, American commanders managed the trick on isolated enemy forces. In 1781 Nathaniel Greene, a Rhode Island pharmacist turned general, led a mixed force of Continental line, militia and irregular forces in the Carolinas. Greene’s simple formula was to win by not losing; he fell back repeatedly while the British under Cornwallis tried to bring him to battle. An isolated British element met with a large American militia force at King’s Mountain in North Carolina and was mauled enough to retreat. The British forces away from Charles Town had no effective supply line, most of it being disrupted by irregulars, and when the British reformed their army near the Cowpens, they were not in the best of shape. Greene formed his army in the best configuration he knew how, providing space for the militia to flee so the Continentals could grapple with the British line, and the result was a British catastrophe. Greene had drawn the British into an isolated trap of overextension while waiting for Washington to arrive with the main army, in the best traditions of American militia. Zachary Taylor took advantage of Mexican isolation at Buena Vista in 1847. Using his superior artillery as a basis of maneuver, Taylor, though outnumbered by at least 2:1, outflanked and outmaneuvered Santa Anna three times in two days. The poorly trained and led Mexican conscripts, cut off from command and supplies of water, easily broke and ran under brutal bombardment by Taylor’s mainly professional force. Only the handful of professionals in the artillery and cavalry managed an orderly retreat. Scott would repeat the pattern of battering the Mexican Army.

War on Places

American strategic theory became formalized only when there was something to work with. The reforms that followed the War of 1812 created the position of General-in-Chief that was so ill defined no one knew quite what to do with it. Winfield Scott, a self-taught officer who had first been appointed a lieutenant by James Madison, penned a translation of a French military treatise and called it Essentials of the Military Art during his tenure. Repeating Jomini, Scott emphasized the then-common European strategic thinking based on the securing of locations as the key to victory. This “war on places” spoke of supply depots, lines of communications, and enemy capitals as being the centers of gravity for any civilized state. In 1861, Scott suggested that securing the Mississippi Valley and blockading her important ports would slowly starve the South. While politically unworkable, it was the first time that any kind of overall plan for an American war had been implemented from the beginning. Henry Halleck, who had written a similar work, took command of Union forces in the Mississippi Valley later that year and worked a strategy of places based on the water and rail transportation network vital not just to restoring the Union, but to the credibility of Southern secession. Without ports, the Confederacy could not communicate with the outside world, and without commerce, diplomatic recognition—a key requirement for nationhood under 19th century law—was nearly impossible.

War on Capacities

During the French and Indian/Seven Years War, irregulars on the frontiers of the American colonies fought each other as they had since Columbus, but there was a difference. The British North Americans realized that irregular “ranger” warfare was the best and most effective, if least efficient, way to strike at the aboriginals sponsored by the other European powers with New World colonies. In the wilds of New York, the Ohio country, the Carolinas and the Great Lakes the Americans were organized, equipped and instructed to take the war to the enemy in their way, to burn fields, destroy towns and take scalps not only to ensure body count but also as a psychological warfare tool. Too, Americans tore at each other’s farms and businesses. Washington used small groups of rangers for reconnaissance and raiding, and did not hesitate to get provisions and arms from British depots in New Jersey by force in 1777, and gladly accepted the bounty of artillery captured at Fort Ticonderoga in 1775. American private warfare against Indians or anyone else emphasized attacks on means of production, military stores, and centers of population. Military campaigns destroyed populations and their means of production to displace them.

Private warfare as national policy.

William Harrison’s fight at Tippecanoe in 1811 began as a raid to destroy the Indian’s spring harvest. In the War of 1812, the Americans barely had time to do much more than hold on to what they already had, but the war against the Indians was prosecuted with an eye towards their corn fields. Andrew Jackson, in the Red Stick War of 1813, spent days burning Indian crops in northern Alabama. This pattern of logistical warfare was repeated throughout the Long War with the Indians. Indeed, the last stand-up battle between Indians and the descendants of the Europeans at Wounded Knee resulted from a dispute over the distribution of rations. The Mexican War was brief, but further showed the American’s tendency to harm their opponents’ capacity to wage war. Scott’s invasion of Mexico carried the war all the way to the enemy’s capital city and its industrial heartland.

The one-sidedness of the result obscured the American logistical strategy

The Civil War was longer and conducted on a much larger scale. Very early, logistics and hindering the Confederate’s capacity to wage war was an important component in Union war aims. The Army and the Navy undertook the blockade of the Confederate coasts jointly, as the Army occupied ports that the Navy would use to make the blockade stronger. The 1864 Meridian campaign, carried out just before the Atlanta campaign began, destroyed the primary small arms and artillery ammunition making areas of northern Alabama and Mississippi, as well as the rail lines that served them. Most importantly, Ulysses Grant gave William Sherman specific orders to locate and arrest any technical personnel that they could find and transport them north under arrest. By 1865, the Southern Confederacy had become a Third World country, bereft (at the moment) of builders needed to manage any industry whatsoever. American military thinkers needed new tools and new imagery to adapt their war capacity to American conditions and the peculiarities of American society’s vision of the role of its land forces. European theories and practices were simply not useful to American armies, and needed serious changes to adapt. Though still somewhat “Napoleonic” in its outlook as late as 1898, the Americans had definitely gone their own way in land warfare doctrine and theory in the 19th century.

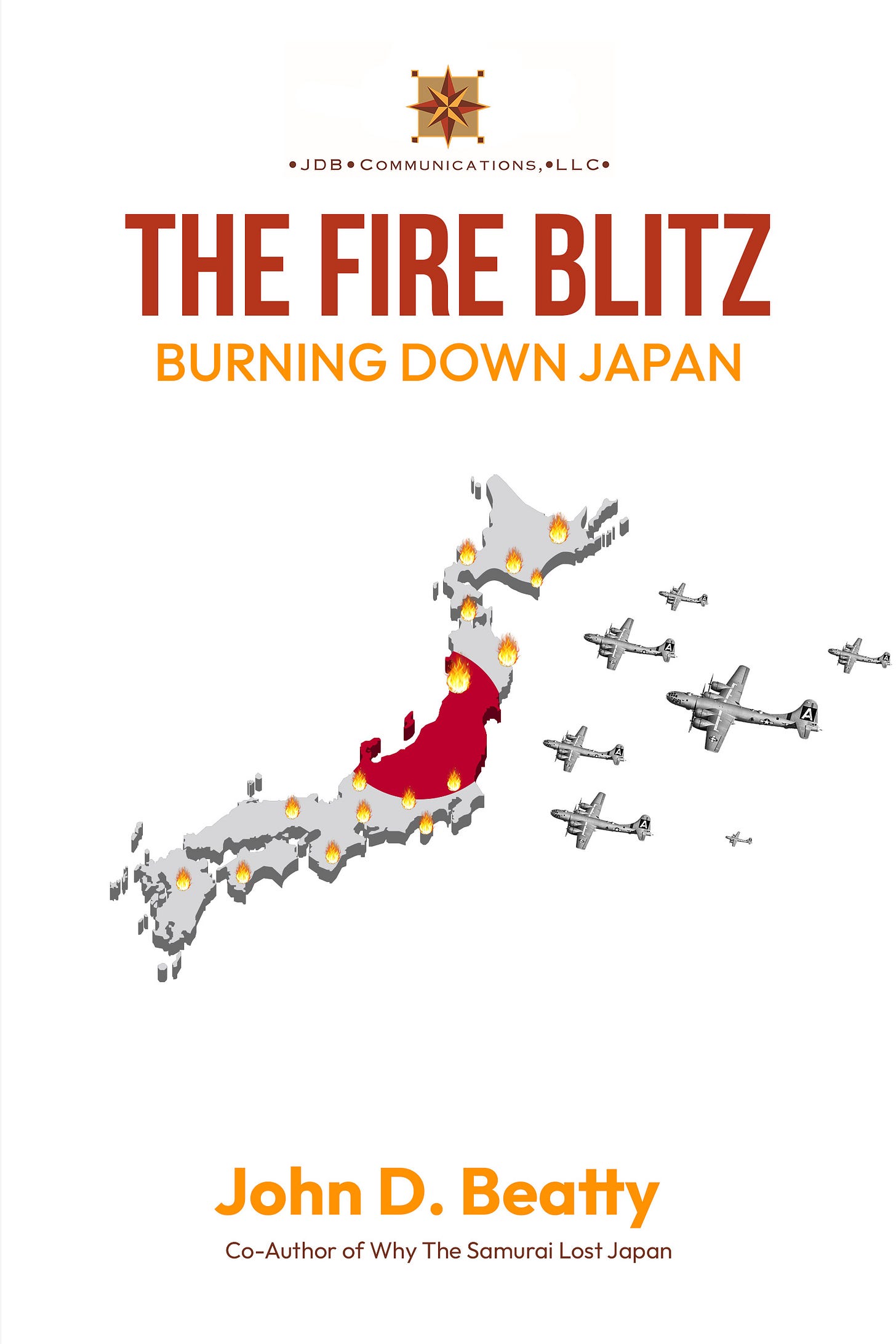

The Fire Blitz: Burning Down Japan

The American bombing campaign against Japan in 1945 was the ultimate expression of American strategic thought. The Fire Blitz and the devastating raids that followed were meant, from beginning to end, to destroy Japan’s capacity to wage war.

Japan’s buildings were primarily wood, making incendiary bombardment that much more devastating, that much more deadly. Available from your favorite bookseller or from me if you want an autograph.

Coming Up…

Six Ways to Rewrite History IV

Mexican-American War Reconsidered

And Finally...

On 21 September:

1866: Herbert George (HG) Wells is born is born in Bromley, England. Most famous for War of the Worlds and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Wells was also a pacifist who, oddly, was a follower of British Fascist Sir Oswald Mosely, and preached against war at every opportunity.

1942: The B-29 Superfortress takes flight in Renton, Washington. Rushed through development and to deployment by “Hap” Arnold, the Boeing behemoths were only to be deployed in a single numbered air force: the Twentieth, in the Pacific Theater.

And today is NATIONAL PECAN COOKIE DAY. Pecans were first domesticated in the American South in the 1830s and thrived on depleted cotton land. Europe was quite mad for them. Its oil had such a high flash point the Royal Navy used it in their warship engines. Lack of availability for pecans was one reason Britain was reluctant to fight the Americans during the Civil War. But…enjoy a cookie, anyway.