From Fillmore's Dilemma To McKinley's Crisis

American 19th Century Pacific Strategy

Like if you want using the keys below; only I can see who you are.

Between the end of the American Revolution and the Boxer Rebellion, American policy and strategic approach to the Pacific Ocean and its multifaceted rim were a distant but omnipresent quandary that engaged the attention and efforts of politicians and traders alike, with varying degrees of success. Confounding any possibility of a simple solution or easy formulae, the North Pacific had been an especially vexing problem requiring both the attention of few and the inattention of many while affecting European power politics, trade relations, diplomatic maneuvering, and even American domestic commercial policies in unexpected ways.

Independence and Trading Partners

The ink wasn't dry on the 1783 Treaty of Paris when Eastern Trader, a Dutch-built American-owned ship, left Portsmouth bound for Canton. Her passengers included three American government officials, along with a Dutch-born language scholar who spoke Mandarin and Cantonese and, apparently, Japanese (though this is unclear). Her cargo included some 2,000 ounces of Spanish silver—about half the specie then available to Congress—a risky proposition with so much of its wealth, but one Congress was willing to take on the chance an agreement with the Emperor of China would pay enough dividends to make it worthwhile.

Ten months later, Eastern Trader dropped anchor in New Bedford, laden with tea, silk, shellac, jade, teak, live rice plants, and a trade treaty signed by the Emperor's envoy. The profits from the voyage were modest for the time—about 150%. The two surviving diplomats sank into obscurity; Eastern Trader was condemned and broken up; the treaty, presented to Congress and filed without debate or ratification, burned when the British sacked Washington. But the China trade had begun, and America had simultaneously gained its first trading partner (China) and its first Pacific rival (Spain). China granted American ships permission to take on water and wood at Chinese ports and to shelter from Pacific storms, providing America with advantages that Spain, controlling the Philippines and other islands, did not seek. The Americans got a similar treaty from the Czarina of Russia in 1788. These events were observed with more than a casual interest by the Great Powers of Europe…and Japan.

The Perils of Manifest Destiny

The whaling trade thrived in the United States after the Revolution, making American ships known in most Atlantic ports before 1800. After the Quasi-war with France (1798-1800), the Louisiana Purchase (1803), and the War of 1812 (1812-15), American whalers appeared regularly in the North Pacific, where only the Russians and Japanese had ventured before. The Americans and Russians used large three-masted ships that could stay out at sea for years at a time, whereas the Japanese usually hunted in sight of land. In 1821, a samurai reported to his shogun (chief warlord who ran what little civil government there was in the Emperor's name), Tokugawa Ieharu, that gaijin (literally long-nosed hairy barbarians) called Yankees had started a brisk trade in fruit and vegetables with some of his fishermen. Such trade violated Japanese law, but the shogun allowed it for the moment, in exchange for information on these Yankees.

Japan was not interested in expanding trade. They had had to put up with the Dutch, the Portuguese, the English and the Spanish and the odd Russian for centuries. Now these Yankees were another bunch who, with the Russians, were interested in whaling in what Japan took to be their turf. Whaling meant large ships could be off Japan's coasts for weeks or even months at a time. Yankee sailors might even land—intentionally or accidentally. The Japanese usually jailed such intruders until they died, or executed them after being humiliated sufficiently to satisfy the local daimyo (overlord). While a few Europeans survived Japanese captivity, they were the exceptions to the will of the Son of Heaven, the Emperor. His will was to only allow trade with the Dutch and Chinese, and all others must die. At least, that’s what the samurai said.

American settlers reached the Pacific from the east in large numbers before 1830, joining the Spanish missionaries and Russian fur trappers already there. The 1846-48 war with Mexico granted the United States the Pacific coast, where whaling interests had already settled a score of harbors. Yankee traders had already profited in furs and lumber and service to the whaling trade, and to supply the gold rush beginning in 1848. Faced with this increased competition, the Russians retreated.

These commercial successes translated into a huge strategic problem way back in Washington: securing the 2/3rds of the country that had practically no one in it but stone-age aboriginals, adventuresome and rich whalers and the tradesmen that supplied them, desperate dreamers with gold in their eyes, and a handful of vagabond trappers.

Communications and logistics in mid-19th century America west of the Mississippi were extremely poor. Any invader of the Pacific coast would have roughly eighteen months of free rein, with no organized American interference—ample time to secure anything worth taking. The still-present problem of shipwrecked New England sailors murdered on Japanese shores, and a fear of the unknown capacity and ambitions of the Japanese compounded this uncomfortable fact. Talking to the Japanese was impossible: they simply refused several American attempts to start contact. In 1837, an American businessman tried unsuccessfully to return three Japanese sailors who had landed on the shores of present-day Washington state. A naval mission in 1846 was unsuccessful in making contact, but another in 1849 saw marginal success. President Millard Fillmore was getting pressure from New England and the Mid-Atlantic states—the source of more than half the votes—to do something to protect their whalers from Japan.

In 1852, Matthew Perry, the Navy's senior ranking officer, took four warships and a mandate from Fillmore: get a trade treaty with Japan by whatever means he deemed necessary. Arriving off Yokohama in 1853, Perry refused Japanese instructions to land at Nagasaki, telling the Japanese that he would fight to land where he wished, and he would speak with an imperial representative. Finally, he declared the Japanese would accept a letter from Fillmore whether or not they wanted to. Perry thereupon departed for China.

What is remarkable here is that, in 1853, there were more Americans who spoke Arabic than Japanese. There had been more non-Muslims who had seen the Qabala by 1850 than there were Anglo-Europeans who had visited Japan and lived to tell the tale. Only the Dutch had had extensive contact: only they understood the state of the Japanese government (such as it was), and their understanding was faulty.

While Perry had done extensive research on Japan, the gap in his understanding of the situation there was extensive. He did not reach a representative of the Emperor Komei, but an envoy of the shogun, the head of the dominant Tokugawa clan. Traditionally, the shogun represented the Emperor, but the fact was that he spoke only for his own clan and interests. When Perry returned to Japan in 1854 with eight warships and threatened to destroy Edo (present-day Tokyo) if the shogun did not sign the Convention of Kanagawa, he signed. While this “opened” Japan to more trade and theoretically stopped the murder of non-Japanese shipwrecked sailors, the other Japanese samurai clans regarded it as an insult.

During this period in Japan, nearly everyone of any significance interpreted the will of the Emperor differently. The inability of the Tokugawas to keep the foreigners away from Japan gave the other clans a wedge other clans could use to force the Tokugawas out of power and restore the emperor to “direct rule,” which would give them more influence and above all, access to His Majesty.

This was how the United States triggered a series of rebellions and civil wars that gradually tore Japan apart and galvanized the samurai leadership.

A Civil War like No Other

This “sudden” thaw in Japanese relations was because of the Tokugawas’ bow to reality. Though they preferred isolation from the rest of the world, common sense told the Tokugawas that they could not keep the world out forever. They had watched China descend into opium-fueled, European-dominated, civil war-riven chaos for decades, and no one in Japan wanted to share her fate. Continued, informal contacts with Russia, the Netherlands and Britain before 1854 had told them that Europe was making great strides in transportation and manufacturing, and that there was much that Japan could learn from them. By 1860, Townsend Harris and other American diplomats had created other treaties with Japan.

But not all Japanese shared that vision for Japan’s future. Rival clans believed that if the Tokugawas persisted in making unreasonable demands on the Emperor to open Japan to the outside world, civil disorder would follow. These filthy invaders directly threatened Japan’s feudal way of life. A few Japanese wanted to keep the invaders out altogether, but this was unrealistic. Most reasoned that it would be better to adapt their weapons and machinery to defeat them, and thus save the Emperor the great distress of having to suffer their presence on Japan's sacred soil.

Both Japan and the United States slipped into civil war at about the same time, only Japan's was practically unknown to the outside world. It spilled over into the world scene in 1863 and again in 1864, at the Shimonoseki Straights between the islands of Honshu and Kyushu. Dominated by a rival to the Tokugawas, the Straights were “closed” to foreign shipping briefly in both years, and each time American and other warships fought the forts and warships to enforce transit rights provided by treaties secured through the Tokugawas. In the 1864 encounter, a multinational force opened the Straights and then burned Edo within sight of the Imperial Palace. That was completely unacceptable to the samurai clans. In each instance, the Tokugawa shogun, acting in the Emperor's name, made even more concessions to the foreigners’ soldier/diplomat forces, although he and his kin took no part in the hostilities. The Japanese had fought both battles with weapons and ships acquired from outside Japan, and the clans were dead set on restoring the Emperor to direct rule (without a shogun) and repelling the invaders. This sonno-joi movement (revere the Emperor and expel the barbarians) triggered more internal violence while the American Civil War was in its last bloody phase.

Mahan and the Unintended Invention of an American Pacific Strategy

After 1865, American foreign policy shifted from simple continental expansion to one of consolidation. Issues in the Pacific included Korea, at the time a troubled Chinese satrap and a haven for pirates, disputes with Russia over the Pribilof Islands off Alaska, and the War of the Pacific (1879-1883) between Chile, Peru and Bolivia. While American diplomats were busy, so were its military theorists.

Both sides of the Atlantic and the Pacific assiduously studied Alfred T. Mahan's The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783 (1890). Europe, Britain and the United States could take advantage of the new idea of “national strategy,” and the gold fields of California and Alaska made a two-ocean navy essential for the US. But in Japan, the situation was foggier.

While Japan had a burgeoning population and breakneck modernization after 1869, her society was still feudal. Universal suffrage was unknown. Her population of roughly 60 million comprised about 5% nobles and samurai…and everyone else. Only one in forty Japanese had ever been inside a bank. The Emperor Meiji (who inherited the throne from his father in 1863) banned the wearing of swords and other samurai traditions in 1869 in theory. But a thousand years of social and cultural conditioning didn’t go away that easily—the samurai clans simply joined the growing army and navy of the imperial state, keeping their traditions for future use but their interests always in mind. The Meiji Constitution, appearing in 1890, made the army and the navy coequal to the civil government of Japan, again in theory, but in practice the samurai were in charge, with the structure of a civil government only for the sake of appearances. “National policy” was what the samurai wanted, not what the government suggested or negotiated with others.

Accidental Empires and Power Politics

By 1890, there were four powers on the Pacific of any significance: Britain, Russia, Spain and the United States. China, humiliated by the all-too-brief Sino-Japanese War of 1894-5, had to wait for the Boxer Rebellion of 1900 to end the sovereignty of the Manchus. Japan’s territorial gains in China from the Sino-Japanese War vanished when France and Germany joined Russia to pressure her to relinquish Port Arthur. This humiliation led to the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, also fought over control of Korea and the Bohai Sea. By the end of 1898, Spain was out of the Pacific, and the US had bases on both sides of the ocean.

But the American presence in the Philippines and Guam bothered the samurai more. They felt surrounded by enemies. Old wounds irritated them, and the humiliations heaped upon them by the Americans in the 19th Century—intentional or not—would engender a decidedly anti-American polity. American protectionism triggered severely limited Japanese immigration into American territory, especially in Hawaii (where ethnic Japanese made up a third of the population in 1900) and California, where nativist movements affected local and national elections after 1900.

Uncertainty about Japanese intentions compelled the Americans to pry open the perennially closed gates of Japan. Political complications, in concert with the operational processes of American politics, forged a clear path to a clash in the Pacific.

The haphazard introduction of phenomenal industrial growth disrupted traditional Japanese feudalism without the benefit of any Enlightenment-driven social reforms. The result was to equip a feudal society with a nearly paranoid worldview with the tools to make modern war against all its perceived interlopers.

The culmination of these factors would ultimately lead to major conflict in 1941.

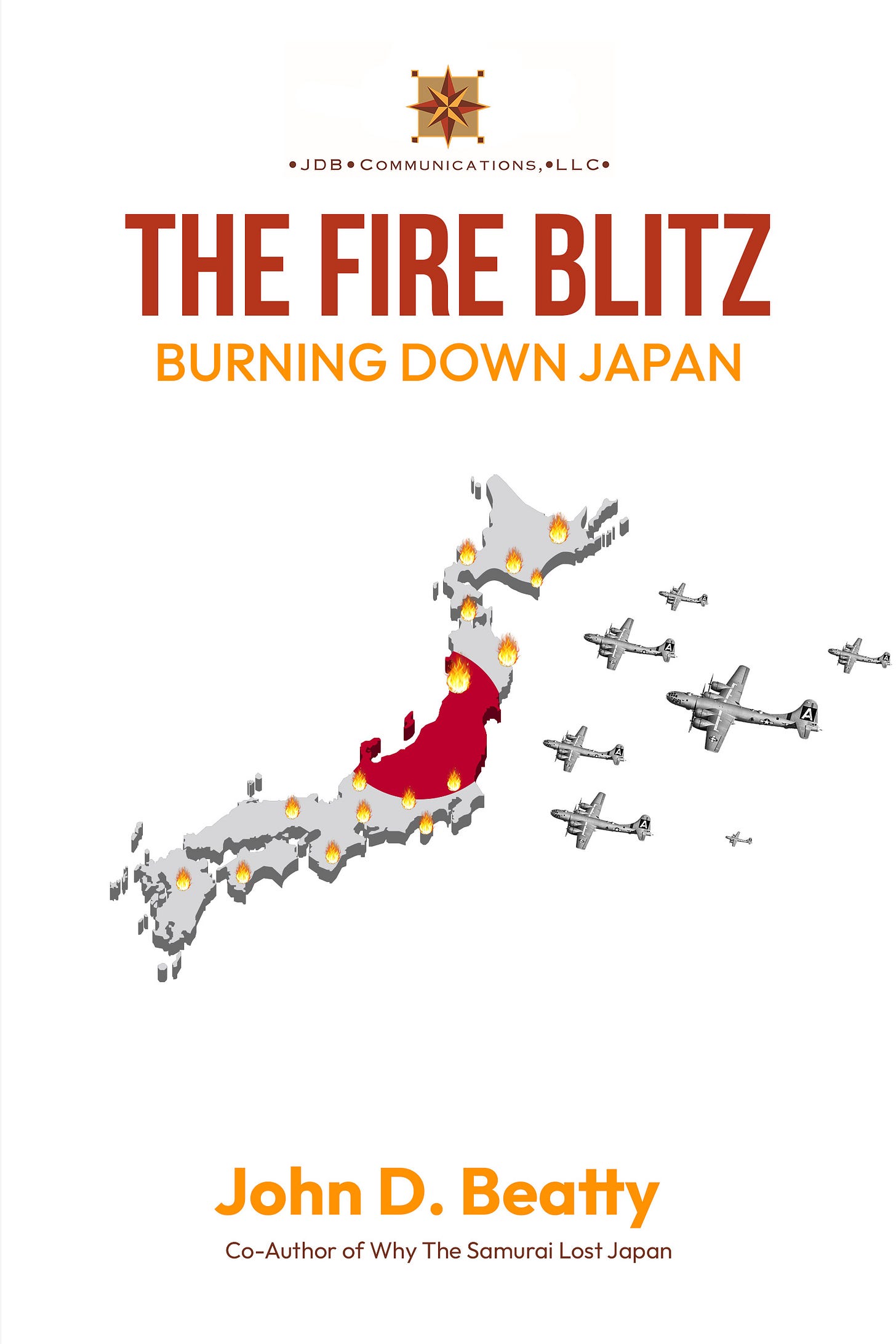

The Fire Blitz: Burning Down Japan

The systematic destruction of Japan’s cities by firebombing was one result of Japanese bellicosity and aggression.

Available from your favorite bookseller or from me if you want an autograph.

Coming Up…

Of Parks and Excuses

Don't Know Much About History

And Finally...

On 25 January:

1947: Al Capone dies on Palm Island, near Miami, Florida. Though he was one of the first Americans to be treated for syphilis with penicillin in 1942, the damage had already been done. After a stroke, pneumonia and heart failure within a week, apoplexy finished Scarface eight days after his 48th birthday.

1969: Peace talks begin in Paris, aimed at ending the American phase of the Vietnam conflict. It became quickly apparent that both sides were using these discussions as political theater, especially after the “Battle of the Tables”—arguments over the shape of the conference tables—raged for nearly two months. It was 1973 before all four factions agreed on a treaty.

And today is OBSERVE THE WEATHER DAY. Why this is in the depths of January, no one is quite certain, because in the Great Lakes, where I am, the weather is just cold and snow.