What Made Japan Do That?

An excellent question, circa 1945

Like if you want using the keys below; only I can see who you are.

Every once in a while, someone in some forum will ask why Japan took on the entire world in 1941, risking everything for want of petroleum. We’ve covered that more than once: they were desperate and gambled.

Fast forward to 1945.

After four years of war with everyone and nearly thirteen years with China and (off and on) the Soviets, Japan was even more desperate than they had been in 1941, and they were running out of both chips and IOUs. The Soviets had not collapsed as expected in ‘42, nor had the British and Americans decided defeating Japan was too costly. Their once-proud and powerful fleet was mostly on the bottom; those ships that survived lacked fuel to leave harbor.

And the killings and sinkings went on.

Some Japanese in Europe had contacted Swiss and American officials—unofficially—with queries about stopping the carnage, getting noncommital responses. There is no evidence Tokyo sanctioned or even knew of these overtures. When Japanese consular officials contacted their masters in Tokyo about such ventures, they met with silence or noncommital answers. It seemed like everyone, including Japan, knew Japan was doomed. But no one in Japan wanted to end the decidedly one-sided fighting.

The “Young Men of Purpose” made sure of that.

Called shishi in Japanese, these majors and colonels infused with bushido spirit and philosophy stalked the halls of power in the War and Naval Ministries, ready to deal with anyone who even hinted at surrendering to the Americans…or anyone else. Even while the lights went out for longer and longer periods every day, they would not countenance any talk of any but ultimate victory or glorious death. As the weeks went on, the cities burned, the people starved and the shortages grew more dire, and the casualty lists grew longer. Even they had to have known victory was clearly out of Japan’s grasp.

That left glorious death.

The why of this irrational ratiocination lies in an understanding of the wartime interpretations of bushido. The old warrior code of Japan has fuzzy origins and even fuzzier margins developed over the centuries, but had roots in samurai traditions that tied them to the code of behavior that they called the “way of the warrior,” bushi-do. Japan’s written laws were few before the 19th Century, and its educated classes were even fewer. “Law” for everyone in a Western sense—even a Chinese sense—was foreign to Japan. Lacking a legal system, there was the samurai who had dominated the archipelago for centuries before Perry came to “open” Japan. The samurai were the bureaucrats, the soldiers, the policemen, and the judges and juries. And they followed bushido.

Bushido: A Code Without Codification.

Many commentators over the centuries wrote and spoke about bushido, but it had no origins in the sense of a founding document or even someone who started it, nor did it have any consistent, written form. Though some writers mentioned the word, few tried to say, “this is bushido.” They talked about the way of bushido—the way of the way of the warrior—but no one tried to tie it down with commandments or prescriptions or even point to an origin. Not until Bushido: The Soul of Japan appeared in 1899—after the samurai traditions were proscribed—did anyone try. The writer, Nitobe Inazō, was an agronomist who never held a sword in battle, was born after Perry arrived in Japan, and died in Canada. While the West held his book in high regard (it was first written in English), Japan regarded it with silence. Nitobe tried to draw parallels between the samurai and Western chivalry and the chivalric codes that simply did not exist. It was this “codification” of bushido that the West had when WWII began.

Tojo Hideki’s version had no parallels with anything in the West.

His fellow generals regarded Tojo as Japan's leading "authority" on bushido before he became both Prime and War Minister. In that capacity, he wrote several treatises on how the Japanese soldier and sailor should conduct himself. It was in his essays-cum-regulations that the soldier was told surrender was dishonorable, that death was required, and that killing all non-Japanese and dying with honor was not just his duty to the Emperor, but to Japan and his ancestors. Tojo also opened the definition of “soldier” and “sailor” to encompass all Japanese. When he became Prime Minister, his version of bushido became the only law worth enforcing.

In Japan, there were no non-combatants.

The civil government became a rump, an ineffectual if constitutionally required appendage the military could ignore. And they did. The Foreign Ministry, which right until December 1941 shadow-boxed at diplomacy with the US, had diplomats and codes and relations with the Soviets and important neutrals, but little function other than obeying the military. The Justice Ministry had police and courts and prisons, but everything they did needed review by the Kempei Tai, Japan’s version of the Gestapo. Even the Agriculture Minister couldn’t publish its statistics without review by the Imperial General Staff for hints of defeatism in the harvests. It was in this atmosphere that America broadcast plea after plea all summer long for Japan to at least talk about ending it in 1945. But though Tojo was out of power, his “code” lived on in the hearts of the young officers he trained, and who still believed. Only the Emperor could—and did—break the deadlock and save Japan from annihilation.

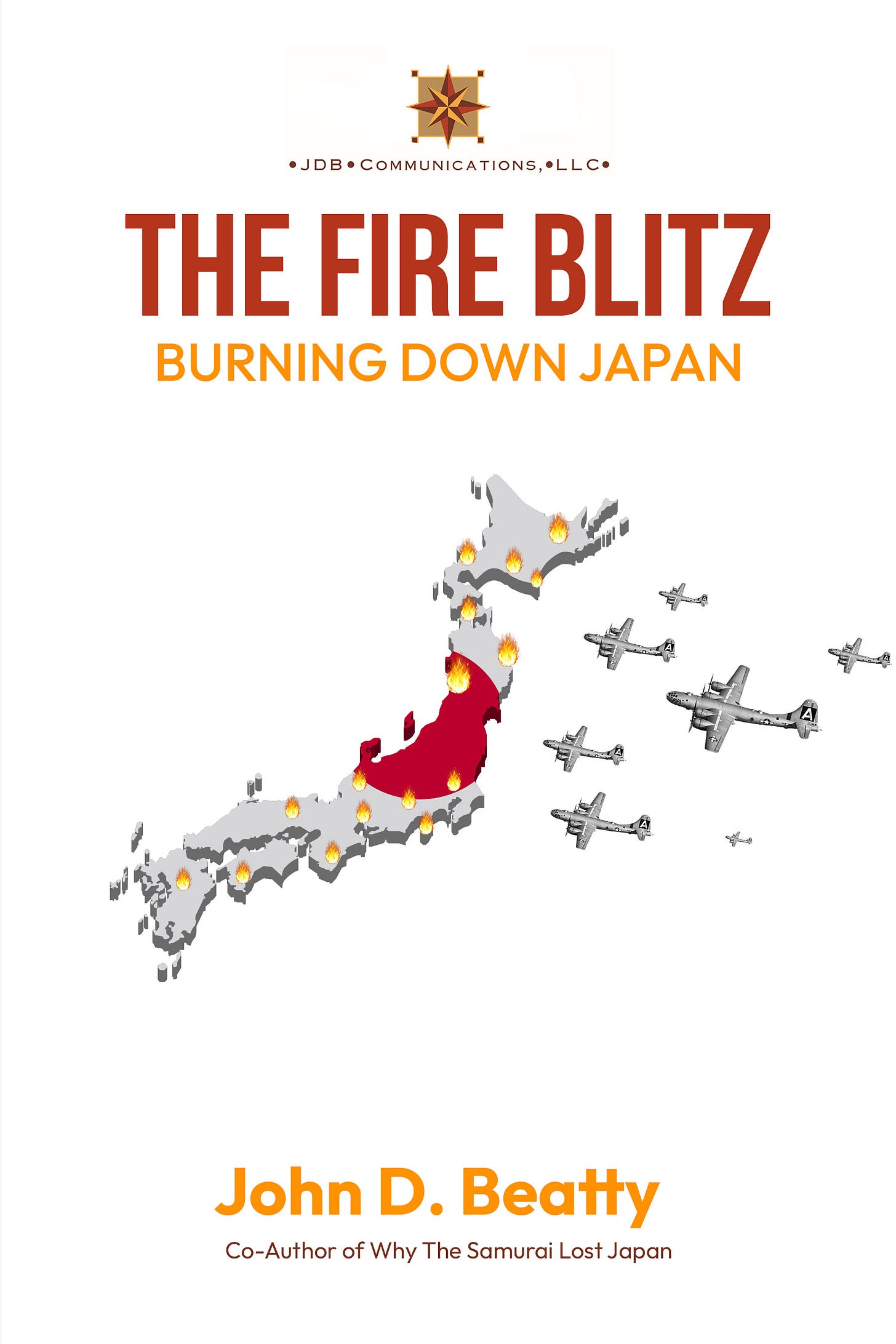

The Fire Blitz: Burning Down Japan

The Fire Blitz was the last, best hope the West had of making Japan just stop fighting in the summer of 1945. Few, while it was ongoing, knew about the atomic bombs, and even those who did knew there would not be enough of them to do the volume of damage LeMay and his clouds of B-29s could do.

In six months, the Twentieth Air Force and its Superfortresses destroyed nearly every industrial target in Japan. If the conflict had not ended in August, the B-29s would not have any more targets left by mid-September. Available from your favorite bookseller or from me if you want an autograph.

Coming Up…

Clare, Shannon, and Me

A Different Horse

And Finally...

On 25 May:

1660: Charles II lands at Dover, England, marking the beginning of the Stuart Restoration of the British monarchy after the execution of Charles II’s father in 1649. This ended the Protectorate/Interregnum, inaugurated a great bloodletting of those who had beheaded the last king, and sewed the seeds of the Glorious Revolution of 1688 that would transform Britain forever.

1977: The George Lucas film, Star Wars, is released in the United States by 20th Century Fox. Later labeled “Episode IV—A New Hope,” this one space opera spawned eight more feature films, “reference” books, novels, short stories, toy and product tie-in lines, several TV series, a magazine, comic books and strips, games, theme park attractions, and even radio dramas. It is the third most lucrative film franchise in history.

And today is NATIONAL MISSING CHILDREN’S DAY, marking the disappearance of the first child whose image appeared on a milk carton, Etan Patz. When his image appeared nationwide in 1984, Etan had been dead for five years.

There's so much more to history than what we think we know. I appreciate all that I've learned from you.