On Winning and Losing

Are events ever so clear cut...outside of games...or are they there?

Both wargamers and historians know there's a difference between victory and defeat; what some don’t appreciate is there's a difference between winning in a game and "winning" in a war.

In neither games nor history, the distinction between winning and losing is neither easy nor clear.

Since Avalon Hill’s Tactics II in 1958, board wargames resolve in some manner of geographic or victory point determination.. Non-wargames of all descriptions have a point system of some description or other (I'm told cricket does—will someone please explain clearly how who gets what points and when?) that determines who buys the first round at the nearest tavern or clubhouse. Even games of chance (as opposed to skill) have a way of figuring out who wins—usually the one with all the money or chips.

Wars—or more properly conflicts—are different.

Not all conflicts end in 1945-style defeat of the key belligerents, dismantlement of empires or occupation of homelands. Very few have ended that way since the end of the Middle Ages. Most conflicts end in such a way that while the shooting stops, the capacity for war is still there, on all sides, and the underlying causes are often unresolved.

Some games treat "winning" abstractly, or ways that aren't winning at all in a historical sense.

A very early case in point was Avalon Hill's Origins of World War II, where when German influence reached a certain level, Jim Dunnigan, the designer, presumed the war to have broken out. With due respect to Dunnigan, a historian looking at this victory condition for the Germans might remark that the opposite was more likely true: if German influence peaked outside of metropolitan Germany, it was not likely that there would have been a war at all. Speculative, but there it is. The original Russian Civil War game by SPI was a multi-player free-for-all, where players competed to become the most powerful Bolshevik at the end of the game. In game terms, clean: in historical terms, not so clean. This meant that the Reds were good for Russia, and that Red victory was inevitable. Really? In these two examples, "winning" is where "game" terms are compared to "real" terms, and the game terms come out wanting.

Games depicting the Thirty Year's War ignore the real loser in the conflict, Germany, which technically didn't even take part as a country.

"Game terms" is a familiar concept to most gamers, and indeed to most people, who like to watch the box scores for their favorite teams. Box scores are ubiquitous, available for any sport in almost any form. It is common knowledge among wargamers that Waterloo was won "on the playing fields of Eton." In brief, “game terms” are modifications that prioritize playability over historical accuracy or simulation.

While they can make for splendid games, they make for lousy history.

In the SPI issue game Operation Cerberus, that covered the Channel Dash of three German warships in 1942, the British player scored a "moral victory" if they scored any hits at all on a German capital ship. (The designer, the late Dale Roethig, was a buddy of mine). The addition of the USS Ranger's carrier air group (my idea) as an optional force (it was available then; Ranger was ferrying aircraft to Malta at the time and left her air wing in England) practically guaranteed such a result. The famous "frontal armor slide" on early editions of AH's Panzer Leader made it hard to destroy armor at any range but point-blank. And if the German 88 mm gun were really as powerful as many tactical games have it, every German company would have had one. These enhancements make game play more entertaining and make the game conform to player expectations.

Unfortunately, "game terms" often get out into the wild where they should not be.

As mentioned in the beginning, few conflicts end with clear-cut victories, and even when they seem to, the end is less "losing" a war than losing some territory. Great Britain didn’t so much "lose" the American Revolution to the colonists as she lost control of some of her North American colonies because of military action undertaken by a coalition that included those pesky Americans. Spain lost overseas holdings to the Americans and a few rebel upstarts in the 1898 war, not in a war where the Americans marched into Madrid. Yet, many people insist that the United States "won" those conflicts in the same binary way that the Allies defeated Germany and Japan in 1945. Also, unfortunately, when there is not ticker-tape parade at the end, these conflicts end up in the "lost" column in the popular imagination; sometimes eventually, sometimes immediately.

The War of 1812, Korea and Vietnam are just three conflicts that are called "lost" by the United States.

Yet, in all three cases, the US fulfilled the original goals. In the War of 1812 (that ended in 1814, New Orleans notwithstanding), the US defined its western borders left ambiguous by the end of the Revolution, and ended impressment of sailors (sort of: the defeat of Napoleon brought the real end to that). In Korea, the end was more ambiguous, but still there is a South Korea that has an elected government, not a dictatorship (which was Truman's original aim). With Vietnam, the US was not a participant in the last battles of 1974-75.

Though the US polity ended in failure, the conflict was "lost" by South Vietnam, not the United States.

Every time Israel survives another conventional attack, it gains a few miles of territory, which somehow becomes "occupied" rather than "taken." But who can say now what the functional difference is between the West Bank of the Jordan and Crimea, which Russia stuck a flag into, and now wants parts of Ukraine, if not all of it? If Israel "illegally occupies" the West Bank that rightfully belongs to the ethnic Arab and Muslim Palestinians, how do we respond to the fact that Jews/Israelis "owned" the area before Mohamed was born? These modern geo-political results and the surrounding controversies typify the demand for binary, game-like results that simply cannot exist in the real world.

Games and real life are different.

Ending many games the same way real life ends or has ended would be unsatisfying and off-putting, resulting in fewer sales, less participation, and an overall downward trend in an industry that is already marginal and dependent on very few discretionary dollars. Thinking of history or even current events in "game" terms is also of dubious value. “Winning” or “losing” a conflict or a game often ends the fighting or playing, but not the arguing over what really happened. As Bernard Montgomery once said, you can lose every battle but the last one.

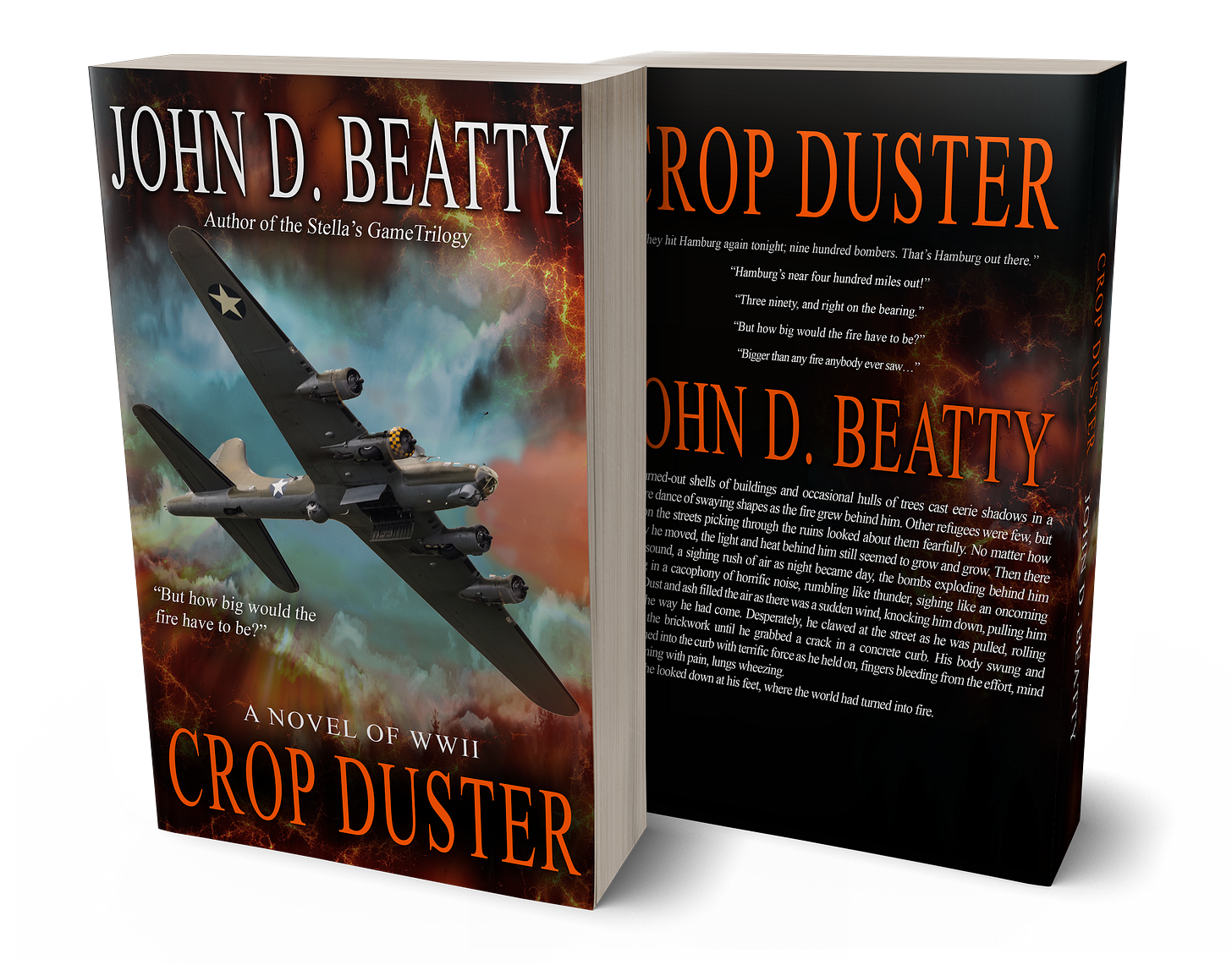

Crop Duster: A Novel of World War Two

The air war over Europe in WWII was…ambiguous…in its effect towards the outcome of the war. Crop Duster shows that ambiguity, along with the feelings of futility on both sides.

While the US and its allies were victorious, the contribution of the Allied strategic air campaign is still controversial, debated to this day. I don’t try to settle that debate; I just talk about a few people amid the splendor and the horror.

Coming Up

What Was Germany's Story Before 1945 that made her so formidable?

Labor Day…And the End Of Summer

And Finally…

On 26 August:

1346: The battle of Crécy is fought between France and England in northwestern France, a part of the Hundred Year’s War. An example of a victory—a decisive English one—that didn’t end its war. The English longbows decimated the French archers and crossbows, while crippling the French mounted knights. They would repeat this in 1415, at Agincourt, between the same belligerents, in the same war.

2020: Wild polio is declared eradicated in Africa. Coming during the COVID panic worldwide, this momentous event went unnoticed by most. While we still see polio in Pakistan and Afghanistan, it is rare in the rest of the world.