Like if you want using the keys below; only I can see who you are.

Great War afficionados will hate this…

What do we say, constructively, about that great ferocious bloodletting that hasn’t already been said? People have been writing about it for a century. What, then, does this poor scrivener trying to sell books add to the corpus of analysis? How about a perspective from a century gone? It all started, as we know, when this guy named Princip shot and killed the Austro-Hungarian crown prince and his wife in Serbia.

Did it, now?

Just why would that one killing lead to the horrors of Verdun and Paashendaele? Well, afterwards, Austria-Hungary got up on its hind legs and said, in sum, “we want this and that and oh, by the way, erase your borders and your sovereignty.” Now, Serbia was a little land-locked country (still is) that barely bordered any part of Austria-Hungary, which was a polyglot “dual monarchy” that could barely control the people it had, let alone taking in the Serbs, not known to be congenial to anyone but their Serb friends, and not even all of them. That, at this distance, looks like an excuse to settle an old score.

So Serbia said…

Yes, to most of the demands, except the one about sovereignty. But Austria-Hungary was determined to get its way. OK, sounds like Austria-Hungary are gonna rumble…so why did Germany and all them get involved? Well, ya see, Russia said it was interested in protecting their fellow Slavs from those big bad Austro-Hungarians. And Germany, being Germany, said “hold on, there, Hoss. Cain’t be attacking my ally down there” (or words to that effect). So now, this little hissy fit over Serbia’s control of her own affairs has turned into a regional hissy-fit over who’s got the biggest whatever.

But then there’s France…and England.

The French had formed an alliance with Russia against Germany in 1902, while Britain used their "splendid isolation" excuse to not ally with anyone as a cover for their ground force weakness (yes, it’s so). But Germany, knowing that France was a bigger threat to them than Russia, at first, had these war plans drawn up by a guy named Schlieffen decades before, that, while looking good on paper, were just that—good-looking paper war plans from a decade before. At their most generous, these plans were good for planning an army or wrapping fish, not launching a continental war. At their most conservative, they required more soldiers than Germany could mobilize in a year. They also required the invasion of Belgium and Luxembourg to invade France, knock them out of the war in a few weeks, then turn everything on Russia, which the plans required to be slow to mobilize. They didn’t address England, which the plans required to stay over there and not interfere with German affairs. But England didn’t think that way, and Russia’s mobilization was much faster than anyone expected.

But why did everyone think like they did?

How did this local shouting match turn into this continent-wide war? Why was little Serbia so important to everyone else? Why was France tied in with Russia? In part, it was a century of rivalry over Africa, over a little fracas in 1870-71 between Prussia/Germany and France, over the revolutions of the 1840s, and over the end of the French Wars in 1815. In short, it was over a continental rivalry between burgeoning Germany and France, between tottering Russia and the powderkeg Balkans, between the crumbling Ottoman Empire and resurgent Italy’s desire for an African empire. And, finally, it was a rivalry between the German Kaiser II and his family in England with all those lovely ships.

And none of them had any idea how destructive their ordnance had become.

While the French Wars ran between 1794 and 1815, there were many breathing periods in between the several “Coalition” wars. The Franco-Prussian War proper lasted only four months of campaigning (the Commune and its aftermath was a different matter). There were several short conflicts in between, not to mention a couple of wars between Japan, China and Russia and that one between Spain and the Americans, and the Italians and Turks, and all those Balkan affairs. But few of them lasted more than a few months of active ground campaigning. Casualties were fairly low…considering who was involved.

But they didn’t look at those conflicts.

By 1914, the relevance of the American 1861-65 “affair” that Europe largely ignored had mostly passed…mostly. While most of the small arms and artillery in the Civil War were muzzle-loading and inaccurate, the logistics behind them were quite muscular, and should have told Europe something. But it didn’t. In 1863, the Union Army spent twenty times the weight of powder it burned in 1861 to create only five times the enemy casualties. This meant that despite the firepower increases of the Industrial Revolution, the power of the defense still held supreme. The Russians largely pioneered the military use of barbed wire in Manchuria in their 1904-5 war with Japan. To breach that wire, the Japanese used human bodies. The handful of Colt, Maxim, and Gatling machine guns used in Cuba were about the number found in a typical German division in 1914. Finally, the money involved in fighting those wars (yes, war costs money) was miniscule compared to what would be needed in 1914. For example, the US spent more money in 1917 just getting the first trickle of soldiers and sailors to Europe (in 1917 dollars) than it had on its entire defense establishment up to 1880.

They didn’t know what they were getting into.

The Industrial Revolution, the Machine Tool Revolution (the revolution that produced the concurrent explosion in precision, accuracy, and volume of production in the late 19th Century) and a Byzantine system of European alliances, both political and emotional, built deadly arrays of armies that were ready to settle old scores at any excuse…and it had been since 1815 since all of Europe had a chance…

Then came Der Tag…

The Germans had been preparing for those heady days in August 1914 for decades, when they could finally get even with their great continental rivals, France, for all the humiliations Central Europe had suffered at their hands. German officers often drank to The Day when that glorious conflict began, when the uhlans would charge gloriously into the blue-and-red ranks and scatter them like wheat before the scythe. France, still smarting from 1871, relished the idea, too. Britain, of course, wanted to make sure that Brittania always ruled the waves and bring the German Navy down to a more manageable size…and protect poor Belgium, of course.

Then came horror after horror.

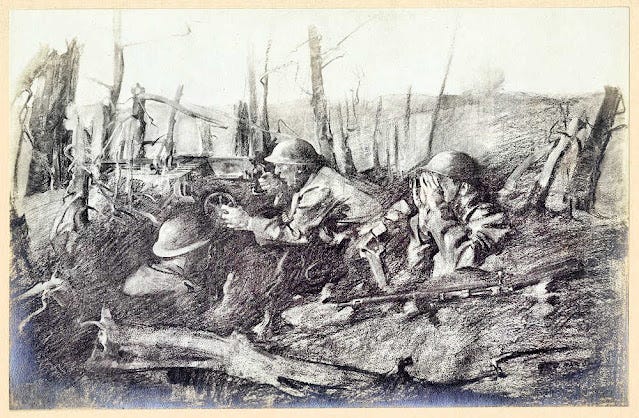

Not only were both artillery and machine guns orders of magnitude more deadly than anyone had expected, they were prodigious consumers of ammunition and thus money. Treasuries emptied faster than anyone expected; armaments factories put on more and more shifts, putting women into industrial plants for the first time to supplement the men…who were dying at a cataclysmic rate in the mud and blood and barbed wire and poison gas and flamethrowers few ever nightmared of. Everyone borrowed money from someone. Submarines torpedoed ships in the wrong place at the wrong time in the dark of night without warning. By late 1916, the economic center of the world had shifted from London to New York, and Britain was asking its gentry to “donate” their gold and jewels to back more loans as conscription loomed and the Irish rebelled. Britain’s blockade, though, reduced Germany to eating turnips as a staple. French soldiers at the front were sacrificing their gas masks to repair their shoes. Russians at the front and at home were making noises about revolution. Austro-Hungarians often barely had five bullets to fire a day. Italian soldiers burned captured rifle stocks for heat.

But it wasn’t all misery.

Women’s attire, and men’s, became practical. As they often did in wartime, fashions changed because of shortages of material and labor. Hemlines went up; the wraparound corset practically vanished, replaced by the brassiere and bloomer-like underwear. Hats, once the dominant feature of women in public, got smaller with every passing year; men were no longer thought to be undressed when hatless outdoors. High-button shoes practically vanished because of shortages of leather and labor. Both sexes suddenly had waterproof coats, sometimes called trench coats that were developed for those conditions. New medical techniques, including vast strides in blood transfusion, treatments for hemorrhagic shock, and thoracic and brain surgery required by the war, saved more lives. For the first time, women could live on their own or provide for their families on their factory-hand salary. Women in Britain and France, long awaiting their liberation, could walk down the street without stockings, smoke in public, and even appear in court to speak for themselves. Automobiles became more common, though gasoline was often scarce. And airplanes, while making the skies more deadly, also made the mail faster and added to the wonders of science and engineering.

But after three and a half years…

Serbia was no more; Austria-Hungary was a shell; Russia was in revolution; Germany was sending 17-year-old boys into the trenches; France had dealt harshly with soldiers too fed up to fight; Britain and Italy were holding on by their teeth. Then the Americans, well-fed, optimistic, and bumbling into their first real global war, came to help the Australians, New Zealanders, and Canadians to break the deadlock of the Western Front while the deadly influenza swept the planet, killing two or three or more times as many people as all the bombs and guns and gas had, in places where the shooting had never been heard.

Then the aftermath.

Europe was broke; four empires smashed with crowns left in the gutter; Japan grabbed the German islands in the Pacific; the Americans, after their horrid casualties to combat and the flu…walked away from Europe (except for the Dawes Plan) and Wilson’s League of Nations as if they had wanted nothing to do with them…and they didn’t. The “peace” that France and England dictated to Germany broke them just enough to cause a boiling resentment that would flash over in 1939, when that war in the margins—where borders are only on maps, and the ties of kinship and politics were strong—would once again break out.

But…

The corset never came back, not in that form; nor did the buttoned shoe revive except for formalwear. Commercial broadcast radio soon took over the airwaves. Women were more empowered than ever before. Overseas transportation boomed with the advent of oil as fuel. Smallpox vaccines became even more ubiquitous, reaching even into Africa, India, and the depths of Siberia on the backs of the flu hunters. Cameras became smaller; the motion picture became better. Electrification of cities became a priority. Horses and their huge infrastructure gradually diminished from urban areas in favor of the bicycle, the truck and the motor car.

But war was even more deadly than it had been in 1914, and few had learned that carrying those grudges from war to war was just insane.

Steele’s Battalion: The Great War Diaries

Steele’s Battalion contains a story upon a story. A scholar finds a diary collection by a soldier—an American Army battalion commander—from World War One. The diarist, one Ned Steele, described his experiences from his commissioning in 1917 to the disbanding of the battalion he created and commanded in 1919. In between, Ned learns about the marriage made in Hell—machine guns and barbed wire—and how to use those machine guns to create that marriage for the Germans.

Steele’s Battalion is still in progress, so no links or covers are available yet. Available from your favorite bookseller or from me if you want an autograph sometime around 6 April 2025.

Coming Up…

George Kenny

Naktong River/Pusan Perimeter Reconsidered

And Finally...

On 3 August:

1914: France and Germany declare war on each other as Germany invades Belgium. Sir Edward Grey, Britain’s Foreign Minister, is said to have lamented: “the lamps are going out all over Europe. We shall not see them lit again in our life-time.”

1958: USS Nautilus, the first nuclear-powered submarine, passes under the North Pole. All nautical achievements need traditions, but Nautilus’ crew needed one for this original feat, so they got a visit from Santa Claus.

And today is NATIONAL GRAB SOME NUTS DAY for no apparent reason other than someone said “hey; let’s call August 3rd Grab Some Nuts Day…no, not those nuts, pervert!” Anyway, go grab some cheap protein.

Best explanation of the runup to WWI that I've ever read. We aren't all historians, so a 'Cliff's Notes' can be helpful.

I just finished reading 'Revolutionary Spring' by Christopher Clark, about the revolts in Europe during 1848. It's very readable and strong on details, but presumes we all have an adequate overview. I don't. Would you care to wade in?