Artificial Intelligence Is Misnamed

They are just programs

Like using the keys below; only I can see who you are.

This is a riff on a Nathan Beacom story in the 7 July 2025 issue of The Dispatch.

Stories in the New York Times and Rolling Stone represent the frightening and far end of the spectrum of chatbot-induced madness.

One man tried to kill a cop with a butcher knife because OpenAI killed his lover.

A 29-year-old mother became violent toward her husband when he suggested that her relationship with ChatGPT was not real.

A 41-year-old now-single mom split with her husband after he became consumed with chatbot communication, developing bizarre paranoia and conspiracy theories.

How many people, we might wonder, are quietly losing their minds because they’ve turned to chatbots as a salve for loneliness or frustrated romantic desire?

Calling chatbots “intelligent” gets the concept wrong.

“AIs” are artificial because humans created them. But they are not intelligent. To call them “artificial intelligence” is to accept not just a fiction, but a bald-faced lie. It is to misconstrue both the nature of machines and of man. It is to give in to how chatbots threaten to atrophy our humanity, and, in extreme cases, even drive us to madness.

I do not feel obliged to believe that the same God who has endowed us with sense, reason and intellect has intended us to forget their use.

Galileo Galilei

We might not all be losing our minds, but there are subtle, pernicious ways in which chatbots affect us. Since their makers present chatbots as personal beings, some inevitably personify or anthropomorphize them. We ask them for help in making decisions, for advice, for counsel. Companies are making a great deal of money by replacing therapeutic relationships with “therapy chatbots” and want to offer “AI” companions to older adults, so that their faraway children need not visit so often. Are you lonely? Talk to a machine. Corporations are happy to endow these programs with human names, like Abbi, Claude, and Alexa.

Don't complain about growing old - many, many people do not have that privilege.

Earl Warren

We become prey to all kinds of manipulation when we uncritically let these machines shape our lives. Chatbots offer relationships without friction, without burden and responsibility. This illusion hampers our ability to engage in the challenge of creating the only things that can give value to human life: genuine bonds with corporeal beings. The more we personify “AI,” the more we slouch toward lives of isolation and deception.

Propaganda does not deceive people; it merely helps them to deceive themselves.

Eric Hoffer

To avoid all this, recognize that there is no such thing as “artificial intelligence”—the very phrase is an oxymoron. The fundamental idea of “artificial intelligence” is a flat-out lie. If we understand what “artificial intelligence” is, we’ll be free from its deceptions, free to cultivate true intelligence in ourselves and others.

Love is the triumph of imagination over intelligence.

Murphy

Confucius thought that truth and honesty must ground the health of human society, and names should match reality as closely as possible. Instead of using the term "artificial intelligence," which is based on a falsehood, we should use language that reflects the reality of what it is. We often understand intelligence today to refer to a certain excellence in carrying out mind-dependent tasks. Thus, when a computer produces similar products to the products of intelligence, we call it “intelligent,” too.

Experience is a hard teacher because she gives the test first, the lesson afterward.

Vernon Law

The famous Turing Test, proposed by mathematician Alan Turing in the 1940s, embodies the idea that intelligence is reducible to task completion. The Turing Test suggests that if a user cannot tell the difference between a machine and a human while communicating with both, the machine is “intelligent.” Some users have become convinced that “AI” tools really are thinking things.

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

Arthur C. Clarke

The Chinese Room is John Searle’s contrary thought experiment that shows how the Turing Test fails as an assessment of intelligence. Imagine two people communicating through a closed door. One knows Chinese, and the other does not. The non-speaker has a set of rules that allow him to match the right response to the characters submitted by the Chinese speaker. The Chinese speaker gets correct written Chinese responses. This Chinese person could become convinced that he is having a genuine conversation, although his partner does not know the meaning of the characters in play and is only following a set of patterns and rules.

Smartphone: a device that connects you to everything while leaving you utterly alone.

Mastroianni and Hart

The Turing Test, like the Chinese room, shows that with adequate rules a machine can “pass” with no understanding at all by merely following a set of rules/programs designed to produce outputs in response to inputs.

This is how every computer works.

No one thinks of a pocket calculator as a thinking, understanding thing. At no point does a calculator understand math or number theory, because understanding refers to the subjective comprehension of a thing. It produces outputs in response to inputs. The most sophisticated computers are just machines that produce outputs based on inputs. Like a calculator, a computer does not literally contain information, have a memory, or think—when we say a computer contains information or memory, we use those terms loosely. The network of very fast switches (transistors, resistors and capacitors) working solely with 0s and 1s responding to electrical charges that are electronic computational devices is a testament to human ingenuity. No matter how complex and well-designed computing processes are, they remain just processes, containing no inherent understanding.

They do not think.

The increased illusion of personality with “AI” over other forms of computation is in its responsiveness. “AIs” use neural nets (presuming an equivalence between circuits and neurons). These models allow the machine to collate statistically significant correlations between data points after data runs through them. If the machine is “trained” (exposed or connected) with enough of the right data to detect regularities, it produces probable responses to inputs according to a program. Large Language Model (LLM) chatbots respond apparently from nowhere, so the huge servers occupying massive warehouses in rural America that the machines run on are invisible, producing the illusion of conversation. But the chatbot is more accurately described as a glorified, very impressive autocomplete program, selecting the next most probable words based on statistical correlations.

Wisdom is what's left after we've run out of personal opinions.

Cullen Hightower

The “AI” behind the chatbot is a dead tool with no desires, personality, or judgment of its own. Its programmers and data access contain its desires, personality, and judgment. The “AI” boosters are trying to fool you. Apple researchers, thankfully, published their findings, bucking this trend, about how the appearance of thought falls apart when LLMs try to tackle certain logic and reasoning puzzles. But AI boosters understand these machines and programs and are encouraging the public to believe AIs can think, relate, and understand the user.

They can’t understand you or their programmer any better than you can understand you.

Instead of “artificial intelligence,” a more accurate name is “pattern engine.” Early computers, which would find mathematical differences, were called “difference engines.” This name adequately recognized the reality of the machine. “AIs” are engines made for aggregating patterns and sorting data into statistical correlations. They sort things into patterns and produce outputs based on the statistical weight of what they sort.

Fact-checking: comparing facts to preferred narratives to label non-compliance as disinformation.

The Muse

A healthy society must be based on truth. And as technological advancement speeds forward faster than we understand and adapt, we can at least avoid being fooled about what’s happening. If this new name catches on, maybe we can use pattern engines in a way that dignifies humanity, rather than degrades it.

A Simple Test You Can Do At Home.

Sometime, when you’ve got nothing else to do, ask an “AI” who the last surviving flag (general or admiral) officer was from World War One. It’s a matter of fact; not a trick question, and almost any American WWI buff/scholar knows the correct answer. If it comes up with any response other than Douglas MacArthur, it’s wrong…or, the response I always get is something like “sorry; can’t help you.” Now, I’m expected to trust the responses from this thing?

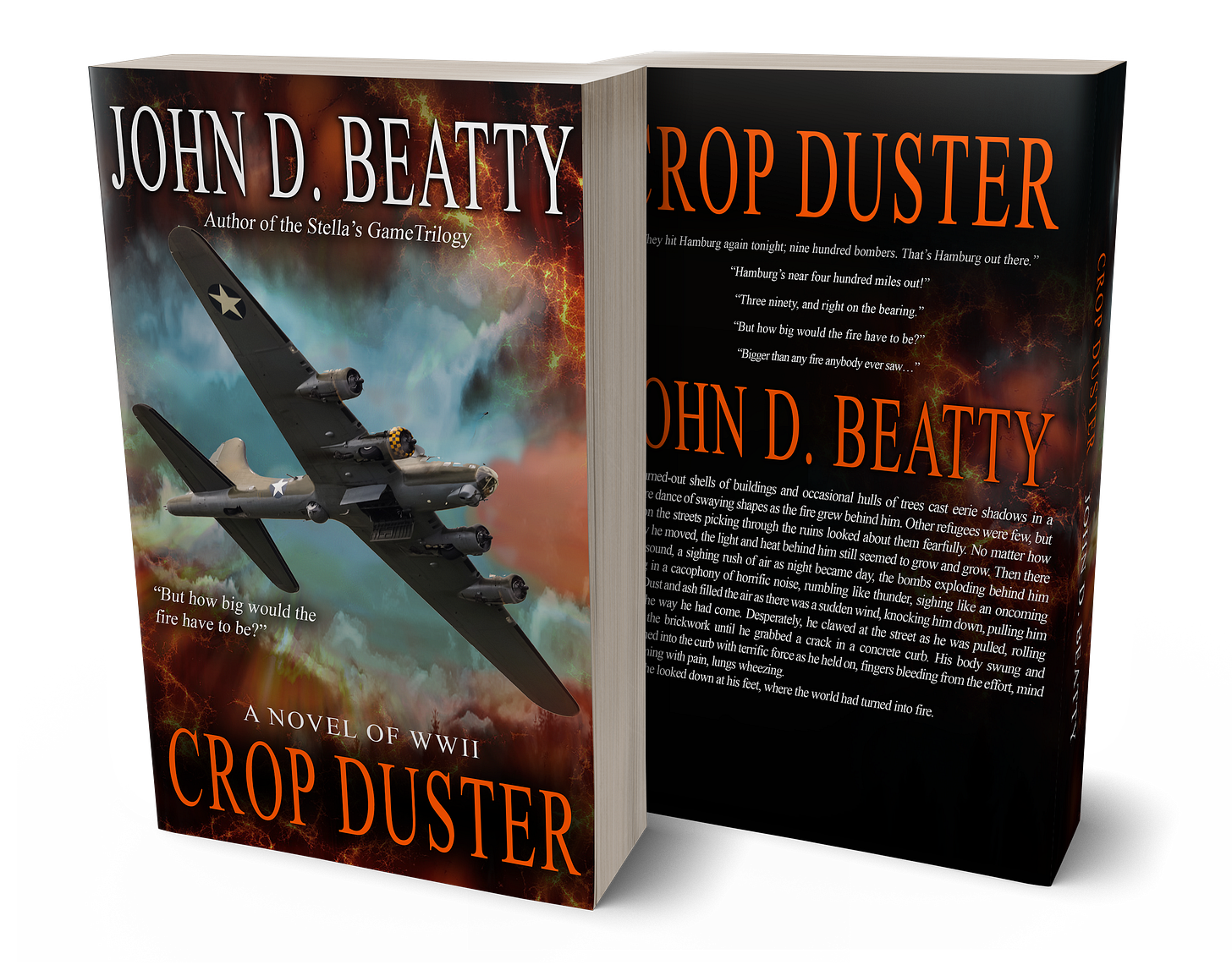

Crop Duster: A Novel of World War Two

There were very few intelligent machines in the skies over Europe in WWII, but there were big, deadly ones, and the men who flew them were pretty bright.

And Finally...

On 25 October:

1840: Helen Blanchard is born in Portland, Maine. With no technical training, Blanchard received 28 patents for her many inventions in sewing technology and is best known as the inventor of the zig-zag sewing machine.

1962: Adlai Stevenson, US ambassador to the United Nations, confronts Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin about Soviet missiles in Cuba in a General Assembly meeting. After displaying photographic proof, Zorin sat mute as Stevenson announced his intention to “wait until hell freezes over” for Zorin’s answer. This was at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis, and near the end.

And today is WORLD TECHNICAL COMMUNICATIONS DAY, observing the death of Geoffrey Chaucer, in London in 1400. Better known for the Canterbury Tales, Chaucer also wrote a detailed manual for using an astrolabe, the first known technical instruction in any language.

"The network of very fast switches (transistors, resistors and capacitors) working solely with 0s and 1s responding to electrical charges that are electronic computational devices is a testament to human ingenuity. No matter how complex and well-designed computing processes are, they remain just processes, containing no inherent understanding."

I'm no neurologist, but our own brains work somewhat similarly. Memories are established electrical circuits in our brain. Our senses are the result of electrical signals sent form various parts of our body to our brains, which processes those signals electrically.

Somehow, from that, we have cognition. Our minds (not our brains, our minds) interpret the information. As a result we can feel the joy of a giggling baby, or feel the fear as an animal attacks. These ae the things that a computer can't do.