Battle of Britain Reconsidered

It wasn't what most people think...

Like using the key below; only I can see who you are.

Many of life's failures are people who did not realize how close they were to success when they gave up.

Thomas Edison

That, or a version of that, is the common view of the Battle of Britain that traditionally started on 10 July and ended on 31 October 1940. The movie version from 1969 had lots of drama and lots of airplanes and did pretty well commercially—you can still see it streaming. That version, like most accounts of the battle, had the doughy RAF challenging the gritty and determined Luftwaffe over the skies of Britain after the collapse of France brought the Germans closer to England, nearly losing the battle in late summer, which was one of the key requirements before the dreaded German invasion. Only the participation of non-British pilots and the German diversion to night attacks on London saved both the RAF and England from certain destruction.

Yeah…no…

The German campaign in France did bring German airfields closer to England. One precondition to the invasion of England was the destruction of the RAF. The British were pretty hard-pressed for most of the summer and early fall. But that was about as accurate as the traditional version gets.

The Battle of Britain was desperate, but Britain’s losing it was not possible.

The Royal Navy's control of the narrow waterways meant German landings were not imminent even if they had destroyed the RAF that summer, which was unlikely. Germany’s surface fleet was negligible in 1940, after losing a third of its destroyers in Norway; it never had enough surface warships to challenge the Home Fleet. The Luftwaffe could attack the RN, but they could not destroy it: it was too big and scattered far out of German range. Second, as William L. Shirer pointed out in his memoir The Nightmare Years, 1930-40, the RAF was bombing the Channel ports of France and the Low Countries almost every night that summer (he saw it), devastating the ships and barges being gathered there. Third, the German Army, having never performed a major amphibious attack before, had a “plan” that kept changing and could never gather the shifting demands for resources, let alone landing craft…and the German Navy wasn’t sure about it, anyway. Fourth, and most definitively, the hydrology of the Channel in summer and fall kept the winds and tides sweeping northwest to southeast, requiring more time to clear the Continental harbors and even more to make a beach landing in England. The air battle over Britain was a desperate attempt to cow England into an armistice—what Hitler wanted and nearly everyone expected, including many people in Britain.

The Battle of Britain was not a prelude to invasion. It could not have been.

By the summer of 1940, the Luftwaffe had fought three major campaigns in less than a year. The pilots were tired; the aircraft were nearly worn out; spare parts were at a premium. Germany designed their air arm only as a ground support and tactical air superiority tool: over the ground battle space and not much farther. They had given no thought to any other major missions, including strategic air superiority or strategic power projection. We can see that by the design of the aircraft, their doctrines and the training of German pilots. Germany’s fighters lacked the range and performance to seriously challenge the RAF over the whole of England. Some generals and planners in the Luftwaffe knew this, but Goering and Hitler didn’t care: the technical details were not their concern.

Only results mattered.

The differences between tactical and strategic are distance and scale. Strategic campaigns are big, sustained, and usually waged at a distance greater than a cannon shot, which does not describe, with few exceptions, the Luftwaffe attacks on England in the summer of 1940. Besides, no one had ever mounted a sustained strategic air campaign before.

That and no one was expecting one.

As suggested above, nearly everyone expected Britain to just give up in the summer of 1940. That Winston Churchill roared defiance while the RAF scrambled to meet the attackers was mildly shocking to Germany and the rest of Europe. France fully expected England to give it up—that was one reason she capitulated the way she did. The Low Countries and Scandinavia expected that their governments-in-exile in London would be short-lived…and didn’t function until the late fall, when the attacks on the RAF airfields in southeastern England eased and the apparent threat ended. While wiser heads in Britain secretly knew that an invasion was highly improbable, they got the entire country to prepare for one anyway, as much to keep them busy as to convince the Americans and the Commonwealth that Perfidious Albion would keep up the fight.

When the Germans started attacking England’s population centers instead of her airfields, the Battle of Britain was over and the Siege of Britain began.

It took some weeks for the Germans to turn the French coastal ports into usable submarine facilities. That and bombers need heavier runways than fighters, and it took weeks to build them, as well. Coupled with the changing weather patterns as 1940 went on, that meant even Germany’s slender invasion plans were impractical. The tools were in place by October for the submarine and bomber campaign that would besiege Britain for the next two years.

And preparations had to be made for Hitler’s next target: Russia.

There, the Luftwaffe would once again come up hard against its limitations of range and endurance, not to mention scale. While the Red Air Force initially was completely outclassed, it was not long before it, too, could command the air over the battlefield. Significantly, the Luftwaffe’s campaign losses over England just might have enabled the Red Air Force’s long-term survival by killing many of its best pilots. With all due respect to my predecessors, the Battle of Britain was important, yes, but it was not decisive. Britain was in trouble, yes, but not danger from the Luftwaffe. The bigger threat was from the U-Boat campaign.

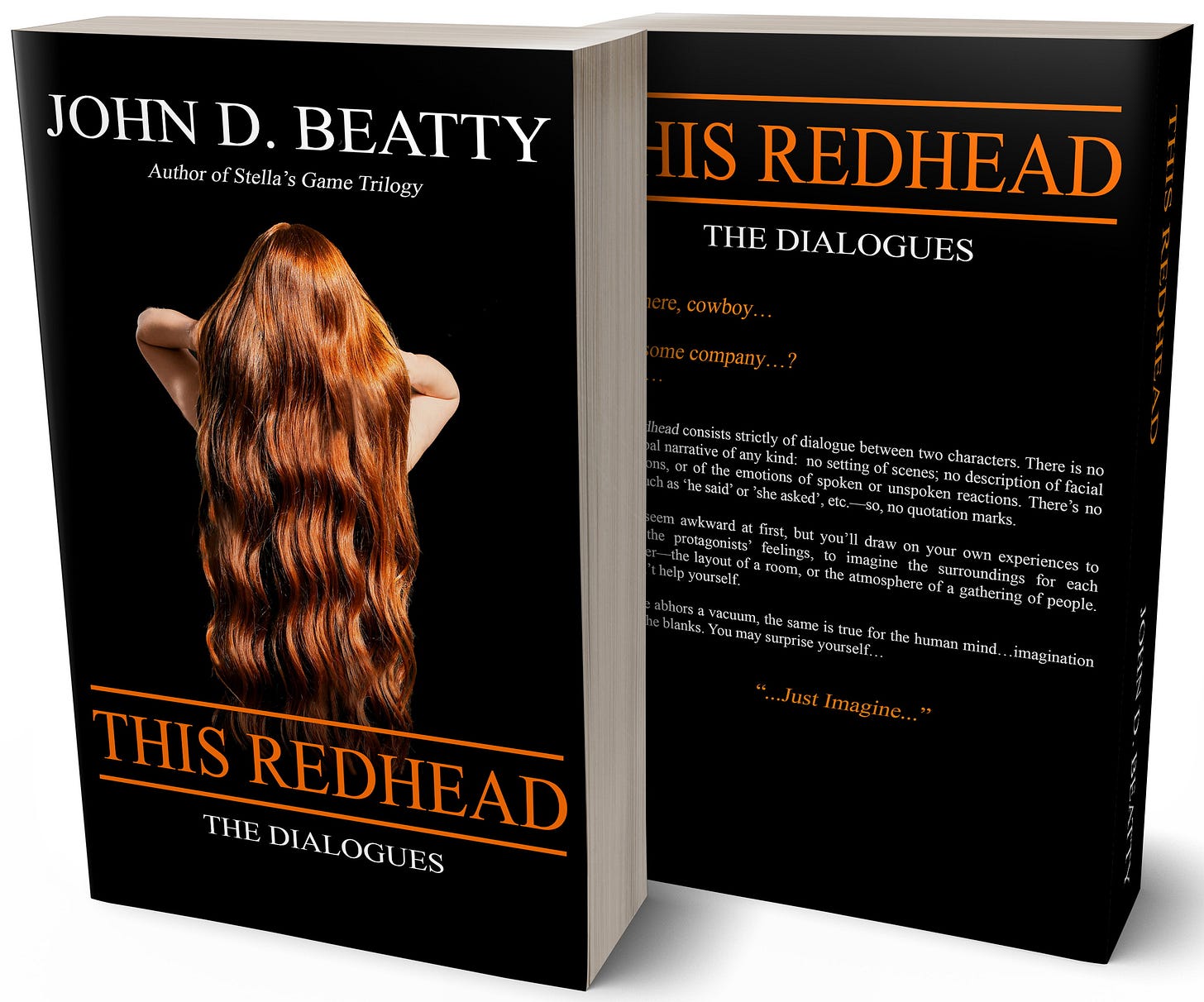

This Redhead: The Dialogues

Nope; This Redhead has absolutely nothing to do with the Battle of Britain or too much of any other battles, campaigns or wars. In fact, it mentions none of them, nor does it even hint at them.

This Redhead, like the Battle of Britain, was an experiment. While the Germans tried to win a war differently, I’m telling a story differently. This Redhead is entirely external dialogue between two people, with no segues, no stage direction, no descriptions that they don’t talk about. All it is, is talk. I just hope it’s more successful than the Luftwaffe was…

Coming Up…

Washington Naval Treaty: The Cruiser Defined…Sort Of

Veteran's Day 2023: Number 100

And Finally…

On 28 October:

1904: St. Louis, Missouri sets up a police fingerprinting bureau. The first such organization in the United States, it followed the increasing use of fingerprints to solve crimes, that started in Argentina in 1892. Fingerprints had been used for identification in India as early as 1832, but law enforcement didn’t start using them until the 1850s.

1967: Julia Roberts is born in Smyrna, Georgia. Unlike most of the actresses in her generation, Roberts was not born on the West Coast and did not study acting in New York. She first achieved notice for the 1990 film “Pretty Woman,” and won Oscar gold for her title role in the 2000 film “Erin Brockovich.”

And today is NATIONAL INTERNAL MEDICINE DAY, celebrating all those brave practitioners who work on our guts, and the rest of us. A big shout-out to my primary care provider and internist, Dr. Karen.