Ronald Knox's Radio Revolution

Didn't change everything, but it changed a lot.

Like using the keys below; only I can see who you are.

This is a riff on Matthew Lyon’s article from the January 2025 issue of History Today.

It was a bitter winter: rivers froze, trains derailed, newspapers went undelivered. But listeners to the BBC on the evening of Saturday, 16 January 1926, were in for a shock when they broke the news that a murderous mob was storming London!

A news bulletin followed a talk about 18th Century literature: London was under attack by a mob of the unemployed! The National Gallery was being sacked, the announcer said, then switched to the weather.

Moments later…an update.

A philanthropist roasted alive in Trafalgar Square! A mortar attack on Big Ben interrupted dance music from the Savoy! The mob hanged the Minister of Traffic from a tramway pole! The mob advancing on Broadcasting House! An explosion cut music from the Savoy short!

Then the report broke off.

Calls flooded newsrooms nationwide. One London hotel alone received 200 telegrams asking if it was safe to visit. In Dublin the next day, milkmen shared the news on the doorstep.

Say what?

Unemployment in Britain ran about 14% for most of 1925-26, so there could have been some truth to it. But did anyone notice that, according to the newsreader, the mob’s fury was driven by Mr. Popplebury, secretary of the National Movement for Abolishing Theater Queues? That the newly established Minister of Transport wasn’t the Minister of Traffic—there was no such office? That all the landmarks mentioned were clearly identifiable to global audiences?

Apparently not.

At least part of the audience either hadn’t heard the early announcement nor the sign-off of a skit by Father Ronald Knox, Catholic priest, novelist and sometime humorist, or weren’t paying attention. The BBC released a transcript of the broadcast, complete with audio descriptions: “Wireless noises bizz, bang, bizz,” and so on. Because the broadcast occurred on a snowy weekend, newspaper delivery was unavailable in much of the UK. The lack of newspapers the next day caused a minor panic, as at least some believed that the broadcast events in London were to blame. In the absence of newspapers, people pestered the police. In May of that year, there would be considerable public disorder during the General Strike that the unions had been talking about for months, so people were open to the possibility of a revolution.

The press had a field day.

“Terror Caused in Village and Towns,” a Daily Express headline blared. “A Blunder by the BBC.” Knox enjoyed the reaction at first, saying he was “almost electrified to learn that Dundee had rung up to know how much of London was left.” But by the end of the week, he was tired of it. Humor, he said that Friday, was our “inestimable playmate ... in the long watches of a hopeless night,” while satire was a beneficent poison.

Broadcasting the Barricades, Knox’s name for the program, wasn’t supposed to be a hoax, but it was an effective one.

Whether he intended his program as play or poison, but he never said, but since it was an announced skit, we have to assume the former. In an interview for his biography This is Orson Welles, Welles said that the BBC broadcast gave him the idea for his own 1938 CBS Radio program, “The War of the Worlds,” based loosely on the HG Wells’ story. Welles’ broadcast led to a similar panic among some American listeners who couldn’t tell the difference between an announced radio play—complete with ads between announced acts—and a genuine news story.

The “revolution” in Knox’s broadcast was in showing the power of mass communications.

That and the persuasive power of apparent authority (he’s on the radio, after all: it must be true). Whisper anything to almost anyone who doesn’t give their full attention to all the facts in any story—like starving children in Gaza who aren’t—and they’ll believe any blowhard with a bully pulpit and an agenda or a yarn to spin and books to sell.

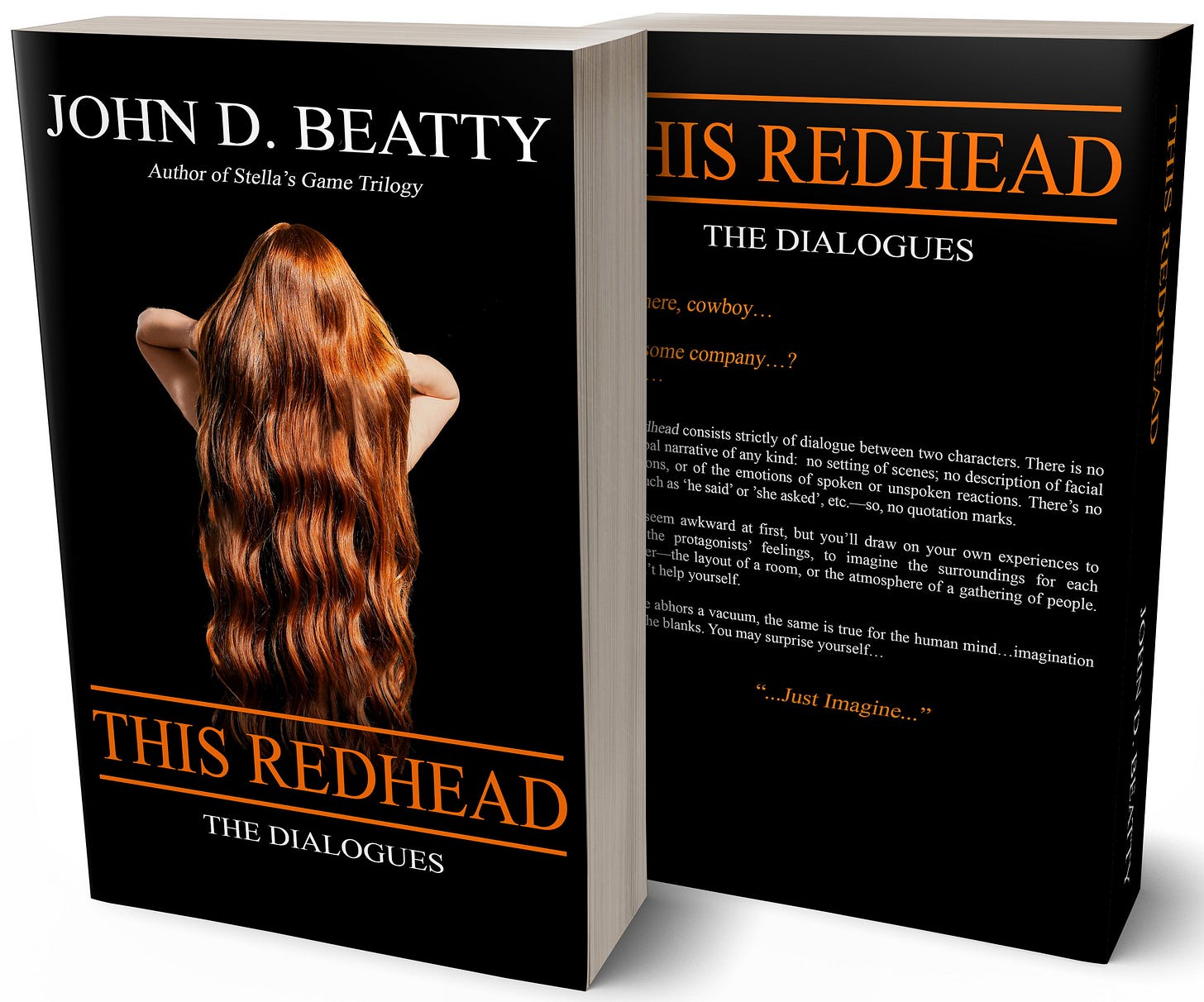

This Redhead: The Dialogues

There’s two things about Redhead that beggar the imagination. The first is that it’s a novel written entirely in dialog—no stage direction, no descriptions outside of what they say. The second is that any part of it actually happened to me, and some parts of it did, indeed.

And Finally...

On 8 November:

1895: Wilhelm Roentgen discovers X-rays in his lab in Würzburg, Germany experimenting with cathode rays. In keeping with today’s theme, these invisible beams of energy could look through soft tissue and create images of bones. He dubbed them X-rays because of their unknown nature.

2016: Donald Trump beats Hillary Clinton for President of the United States. It was difficult for many to believe that a real estate mogul and reality TV star could defeat a former First Lady, one-term Senator (with no bills to her name) and one-term Secretary of State (with no treaties or foreign policy initiatives to her credit) in a national election. Many had trouble believing it for years after; some still don’t.

And today is NATIONAL TUBE TOP DAY, commemorating this day in 1973 when Elie Tahari first marketed the elasticized (as opposed to tied) tube top as a women’s fashion accessory in New York. The first soon-to-be sensational tubes resulted from a manufacturing mistake in elasticized gauze bandages that Tahari scooped up, re-cut, tested, copied with different fabric colors and marketed to women, though something like them had been around for girls since the ‘50s.